Three Wise Men? The Christmas Lie We’ve Been Telling for 2,000 Years

The Nativity Scene in Your Living Room Is Wrong

Every December, they appear. On mantels, in church lobbies, under Christmas trees across America. Those little nativity figurines: Mary, Joseph, baby Jesus in the manger, some shepherds, a few animals, and—always, always, always—three wise men.

Three kings, often labeled Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar. One typically depicted as European, one African, one Asian—representing the whole world coming to worship Jesus. Three distinct figures bearing three gifts: gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

It’s iconic. It’s traditional. It’s been the standard depiction for centuries.

It’s also completely made up.

The Bible never says there were three wise men. Never. The Gospel of Matthew, which is the only Gospel that mentions the magi at all, doesn’t specify a number. Not three. Not two. Not twelve. Just… magi. Plural. More than one. That’s it.

So where did “three” come from? Why is it so deeply embedded in Christian tradition that even suggesting a different number feels heretical?

The answer reveals something fascinating about how religious traditions develop, how symbolism overtakes history, how art and culture shape belief more powerfully than scripture itself.

We made up three wise men because of three gifts. That’s it. That’s the whole reason.

Someone, somewhere, centuries ago, saw that Matthew mentions three gifts and thought: “Three gifts? Must be three gift-givers!” And that interpretation stuck so thoroughly that now suggesting there might have been two magi, or seven, or twenty feels like you’re ruining Christmas.

But here’s the thing: the actual biblical account is way more mysterious, way more interesting, and way more theologically rich than our sanitized nativity scenes suggest.

The real story of the magi isn’t about three kings following a star. It’s about unknown numbers of mysterious foreigners showing up to worship a Jewish baby, guided by astronomical phenomena we can’t fully explain, bringing gifts loaded with symbolism that foreshadow Jesus’ entire life and death.

That’s a much better story. We just had to domesticate it with our obsessive need for tidy details.

What the Bible Actually Says (Spoiler: Not Much)

Let’s look at what Matthew’s Gospel actually tells us about the magi, because it’s surprisingly sparse:

“After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, during the time of King Herod, Magi from the east came to Jerusalem and asked, ‘Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews? We saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.'”

That’s the introduction. “Magi from the east.” Plural, but no number.

They visit Herod, who freaks out about a rival king and asks his advisors where the Messiah is supposed to be born. The advisors say Bethlehem, based on Old Testament prophecy. Herod tells the magi to go find the child and report back (spoiler: they don’t).

“After they had heard the king, they went on their way, and the star they had seen when it rose went ahead of them until it stopped over the place where the child was. When they saw the star, they were overjoyed. On coming to the house they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.”

Notice: They find Jesus in a house, not a stable. This happens some time after his birth—weeks, maybe months, maybe up to two years based on Herod’s later actions. And they bring three types of gifts.

That’s the entire account. No names. No number. No description of what they looked like or where exactly they came from. Just “magi from the east” who followed a star, found Jesus, gave gifts, and left.

Everything else—the three kings, the names, the ethnicities, the elaborate journey, the detailed nativity scene—is tradition piled on top of a very brief biblical account.

Who Were the Magi Actually?

The word “magi” (singular: magus) doesn’t mean “kings.” It refers to a class of Persian priests and scholars known for studying astronomy, astrology, and what we’d now call natural philosophy.

These were educated elites from the Parthian Empire (modern-day Iran/Iraq region) who tracked celestial events and interpreted their meanings. They were astronomers and astrologers, counselors to rulers, keepers of knowledge.

They were definitely not Jewish. They were Gentiles—foreigners—which makes their appearance in Matthew’s Gospel theologically significant. The very first people to worship Jesus as Messiah and king, according to Matthew, were foreign scholars guided by astronomical observation rather than Jewish scripture.

That’s huge. It signals that Jesus’ significance extends beyond Judaism to all nations. The magi represent the Gentile world recognizing Christ.

But the biblical account doesn’t glorify them or give them elaborate back stories. They’re mysterious foreign wise men who show up, worship, give gifts loaded with symbolic meaning, and disappear from the narrative entirely.

Later Christian tradition transformed them into kings. Why? Partly because Old Testament prophecies about the Messiah mention kings coming to worship him. Partly because it made the story more impressive—if even kings worship this baby, he must be really important.

But “magi” and “kings” are different things. The magi were scholarly priests, not royalty. The transformation happened over centuries as the story was retold, embellished, and adapted to serve theological and cultural purposes.

The Three Gifts (And Why They Matter More Than the Number)

Let’s talk about why those three gifts are actually significant—way more significant than the number of people carrying them.

Gold = Kingship. This is a gift for royalty. By bringing gold, the magi acknowledge Jesus as a king. This is political and dangerous—there’s already a king (Herod), and here are foreign dignitaries recognizing a rival.

Frankincense = Divinity. Frankincense was used in temple worship, burned as incense to honor God. By bringing frankincense, the magi acknowledge Jesus isn’t just a human king but has divine status. This is theologically loaded.

Myrrh = Death. Myrrh was used for embalming bodies. It’s a burial spice. By bringing myrrh, the magi—perhaps unknowingly—foreshadow Jesus’ death. This baby they’re worshiping will die, and his death will matter.

So the three gifts tell a complete story: Jesus is a king (gold), he’s divine (frankincense), and he will die (myrrh). That’s the entire gospel in three symbolic presents.

The number three matters symbolically—it represents completeness, the Trinity, divine perfection. Three gifts, three aspects of Jesus’ identity and mission.

But that doesn’t mean three gift-givers. You could have seven magi pooling their resources to buy three types of gifts. You could have two magi with three gifts. The gifts’ symbolism works regardless of how many people brought them.

We assumed three magi because of three gifts. But that’s not biblical—it’s just a convenient assumption that became tradition.

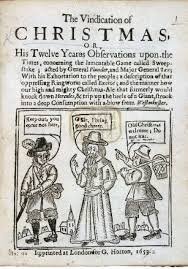

How Tradition Invented Three Kings

So how did we get from “magi from the east” to “three kings named Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar”?

Gradually, through centuries of artistic representation, theological speculation, and cultural elaboration.

Early Christian Art (3rd-4th centuries): Depictions of the magi varied wildly. Some showed two visitors. Some showed four. Some showed six. Some showed twelve. Artists were just illustrating the biblical account with whatever number felt right compositionally.

Medieval Period: The number started settling around three, probably because of the three gifts. By the 6th century, three had become standard in Western Christian art and tradition.

Names and Ethnicities: These came even later. The names Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar appear in medieval legend, not biblical text. The tradition of depicting them as representing different races (European, African, Asian) developed to symbolize the universality of Christ’s kingship—all peoples worshiping him.

Cultural Elaboration: Over centuries, elaborate stories developed around the magi. Where they came from. What they discussed on their journey. How they knew to follow the star. What happened to them after leaving Bethlehem.

None of this is biblical. It’s all cultural tradition building on a very spare biblical foundation.

And here’s what’s fascinating: these traditions became so powerful that they essentially replaced the biblical account in popular understanding. Most Christians couldn’t tell you what Matthew’s Gospel actually says about the magi—they can only describe the traditional elaborated version.

Tradition didn’t just interpret the biblical account—it overwrote it.

Why We Can’t Let Go of Three

Okay, so the Bible doesn’t say three. Early Christians didn’t agree on a number. “Three” is just tradition.

So why does suggesting a different number feel wrong? Why do we cling so tenaciously to three wise men?

Symbolism: Three is a powerful number in Christian theology. Trinity—Father, Son, Holy Spirit. Three days between crucifixion and resurrection. Three theological virtues (faith, hope, love). Three magi fits this symbolic pattern beautifully.

Completeness: Three feels complete in a way two doesn’t and twelve feels excessive. Three is just right—enough for diversity, not so many you can’t keep track.

Art and Culture: We’ve been depicting three magi for over a thousand years. Every nativity scene, every Christmas pageant, every artistic representation. That visual tradition is incredibly powerful. Changing it feels like vandalism.

Names and Personalities: Once the magi got names and distinct characteristics (one old, one middle-aged, one young; one European, one African, one Asian), they became characters rather than anonymous figures. Characters are harder to multiply or reduce.

Cognitive Ease: “Three wise men” is simple to remember, teach children, and depict. “An unspecified number of magi” is complicated and unsatisfying. We like tidy answers.

Tradition as Authority: For many Christians, centuries of tradition carries weight comparable to scripture. If the Church has depicted three magi for a thousand years, changing that feels presumptuous—who are we to override centuries of Christian practice?

But here’s the tension: valuing tradition is important. Traditions connect us to past generations, embody theological wisdom, provide continuity and meaning.

But when tradition becomes more authoritative than the actual biblical text it’s supposedly based on, something’s gone wrong. When “we’ve always done it this way” overrides “here’s what the text actually says,” we’re prioritizing human invention over divine revelation.

The Mystery We Sterilized

Here’s what really gets lost when we insist on three wise men with names and ethnicities and tidy backstories:

The mystery. The strangeness. The openness to wonder.

The biblical account is mysterious. Who were these magi? How many? From where exactly? How did they know the star’s significance? Did they understand who Jesus really was, or just recognize something cosmically important was happening?

We don’t know. Matthew doesn’t tell us. And that not-knowing creates space for imagination, for wonder, for recognizing that God works in ways we can’t fully comprehend or control.

By filling in all the details—three kings, here are their names, here’s where they’re from, here’s exactly what happened—we’ve domesticated the story. Made it manageable. Turned mystery into trivia.

But the original account isn’t trivia. It’s genuinely mysterious: foreign scholars, guided by astronomical phenomena, traveling long distances to worship a Jewish baby in occupied territory, bringing gifts that foreshadow his entire mission, then vanishing from the narrative.

That’s weird and wonderful and theologically rich precisely because it’s not fully explained.

When we insist on knowing exactly how many magi there were, we’re trying to control a narrative that’s supposed to evoke wonder. We’re replacing “we don’t know, isn’t that amazing?” with “we made something up and now defend it like it’s fact.”

What the Number Doesn’t Matter For

Here’s the thing: whether there were two magi or three or twelve doesn’t change anything theologically significant.

The point of the magi’s visit isn’t their number—it’s what their visit represents:

Gentile Recognition of Christ: Non-Jews worshiping Jesus signals his universal significance. This matters regardless of how many Gentiles showed up.

Guided by Creation: They followed a star, meaning God revealed Christ through the created order, not just through scripture. This works whether two or twenty followed the star.

Symbolic Gifts: Gold, frankincense, and myrrh tell Jesus’ story—king, divine, mortal. The symbolism is complete regardless of how many people carried the gifts.

Contrast with Jewish Leaders: Foreign magi seek Jesus while Jerusalem’s religious establishment ignores him. This ironic reversal works no matter the magi’s number.

Fulfillment of Prophecy: Old Testament hints that nations would recognize Israel’s king. The magi fulfill this whether they’re a small or large group.

The theological significance is entirely independent of the number. Which means obsessing about the number misses the point.

We’re arguing about trivia while ignoring the actual meaning of the narrative.

Modern Implications (Yes, This Still Matters)

You might think: “Who cares? It’s a minor detail about an ancient story. Does it really matter if we say three wise men when the Bible doesn’t specify?”

Fair question. Here’s why it matters:

Biblical Literacy: Most Christians don’t actually know what the Bible says because they’ve confused tradition with scripture. They think the Bible says three wise men because that’s what they’ve always been told. This reflects broader biblical illiteracy where people believe things are “in the Bible” that absolutely aren’t.

Authority Questions: If we can’t distinguish between “the Bible says” and “tradition says,” we can’t evaluate what actually has divine authority versus what’s human invention. This matters enormously for all doctrinal and ethical questions.

Intellectual Honesty: Claiming “the Bible says three wise men” when it doesn’t is simply false. If we care about truth, we should care about accuracy—even in small details.

Room for Mystery: Insisting we know things the Bible doesn’t tell us reveals discomfort with uncertainty. But faith requires some comfort with mystery, with not-knowing, with trusting God even when we don’t have all answers.

Tradition’s Proper Role: Tradition is valuable but not infallible. It should illuminate scripture, not replace it. The three-wise-men tradition shows how traditions can become so entrenched they override the actual biblical text.

So yes, it matters. Not because the specific number changes theology, but because how we handle this question reveals how we handle authority, truth, tradition, and mystery.

Embracing the Unknown

So here’s my proposal: What if we embraced the mystery?

What if we admitted: “The Bible doesn’t tell us how many magi visited Jesus. We don’t know. And that’s okay”?

What if nativity scenes came with little question marks where the magi’s number should be?

What if we taught children: “We call them three wise men because of three gifts, but Matthew’s Gospel doesn’t actually say how many there were. Isn’t that interesting?”

What if we saw the not-knowing as a feature, not a bug—an invitation to wonder rather than a gap requiring filling?

This doesn’t require abandoning tradition. You can still put three figures in your nativity scene. You can still sing “We Three Kings” (though note: that song admits they’re not actually kings—”We three kings of Orient are / Bearing gifts we traverse afar”). You can still appreciate centuries of artistic representation.

You’re just honest about the distinction between biblical text and traditional interpretation.

And that honesty creates space for:

Intellectual integrity: We don’t claim to know things we don’t actually know.

Deeper engagement: Instead of assuming we know the story, we actually read what Matthew wrote.

Theological richness: We focus on what the magi’s visit means rather than trivia about their number.

Comfort with mystery: We model that faith doesn’t require having every answer nailed down.

Better biblical literacy: We help people distinguish scripture from tradition.

None of this ruins Christmas. If anything, it enriches it—by inviting us to engage more thoughtfully with the actual biblical narrative rather than our domesticated version of it.

The Magi We Need

Maybe what we need isn’t three wise men with names and backstories and neat explanations.

Maybe we need mysterious foreign scholars following astronomical signs to worship a baby in a backwater town, bringing gifts that tell his whole story, then disappearing without explanation.

Maybe we need the version that doesn’t fit our tidy categories, that resists our compulsion to fill in all the blanks, that stays strange and wondrous.

Maybe we need to remember that the Christmas story isn’t supposed to be comfortable and domesticated. It’s supposed to be shocking: God becoming human, born to a teenage mother in occupied territory, worshiped by foreign astrologers, threatened by a paranoid king, saved by fleeing to Egypt as a refugee.

That’s not a cozy story. It’s dangerous, subversive, mysterious.

The three-wise-men tradition—with names and ethnicities and detailed journeys—makes it manageable. Safe. Something we can replicate in miniature on our mantelpieces.

But the actual biblical account resists that domestication. It’s sparse, mysterious, open-ended. And maybe that’s exactly what we need—a story that doesn’t give us all the answers, that leaves us wondering, that invites engagement rather than passive consumption.

The Ending That Isn’t

So how many wise men visited Jesus?

We don’t know.

The Bible doesn’t say.

Tradition says three.

Art has depicted three for centuries.

But the actual answer is: we don’t know, and that’s okay.

The magi came. They were foreigners, scholars, guided by astronomical observation to worship a baby. They brought gifts loaded with meaning about who Jesus was and what he’d do. Then they left, warned in a dream not to return to Herod.

That’s the story. Everything else is elaboration.

And maybe instead of defending our elaborations as though they’re biblical fact, we should:

- Be honest about what scripture says and doesn’t say

- Value tradition without elevating it above scripture

- Embrace mystery instead of insisting on tidy answers

- Focus on theological meaning over trivial details

- Model intellectual integrity in how we handle sacred texts

Your nativity scene can still have three wise men. I’m not the nativity police.

Just know that “three” is tradition, not scripture. An ancient, beautiful, meaningful tradition—but tradition nonetheless.

And sometimes acknowledging what we don’t know is more faithful than pretending we know more than we do.

The magi came to worship Jesus. That’s what matters.

How many came?

We don’t know.

And you know what? That’s actually kind of beautiful.

Merry Christmas. May your celebrations be filled with wonder, mystery, and honest engagement with the stories that shape us.

Even when—especially when—those stories resist our need for tidy answers.