The Time England Literally Canceled Christmas (And People Lost Their Minds)

Oliver Cromwell's Puritan-led Parliament decided that Christmas

When Puritans Ruined the Holidays

Imagine waking up one morning to discover that your government has officially banned Christmas.

Not just discouraged it. Not just frowned upon excessive celebration. Actually made it illegal to celebrate the birth of Christ during the season traditionally devoted to celebrating the birth of Christ.

No church services marking the day. No feasting. No decorations. No time off work. Anyone caught celebrating faces fines or worse. Christmas, as you’ve known it your entire life, is now a crime.

This isn’t dystopian fiction. This actually happened in England in 1647, when Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan-led Parliament decided that Christmas was too fun, too excessive, and too Catholic—and therefore had to go.

The result? Exactly the chaos you’d expect when you try to abolish people’s favorite holiday.

Secret Christmas gatherings. Underground festivities. Open defiance. Riots in some towns. Pamphlets circulating that denounced the government’s overreach. A black market in Christmas pies and mince, because apparently Puritans could ban the holiday but couldn’t stop people from wanting festive food.

The story of Christmas under Cromwell is wild, revealing, and surprisingly relevant today—a case study in what happens when religious zealotry meets political power, when cultural tradition collides with ideological purity, and when a government decides it knows better than the people what they should be allowed to celebrate.

Spoiler alert: the government lost. Christmas survived. But the fight was messier than you’d think.

The War That Changed Everything

To understand why Christmas got canceled, you need to understand the English Civil War—which is basically what happens when political, religious, and economic tensions build for decades until everything explodes spectacularly.

On one side: the Royalists, supporting King Charles I, the Anglican Church, and traditional hierarchies. Generally more comfortable with religious ritual, celebration, and the old ways of doing things.

On the other: the Parliamentarians, dominated by Puritans who believed the Church of England hadn’t gone far enough in reforming away from Catholicism. They wanted to strip away anything that smelled of “popery”—elaborate rituals, excessive celebration, any religious practice not explicitly commanded in scripture.

When the Parliamentarians won and Oliver Cromwell took power, they had the opportunity to remake England according to their vision. And their vision was… austere. Very austere.

The Puritans believed English society had become morally corrupt, that people were too focused on pleasure and not focused enough on God. Their solution? Regulate everything. Make society morally pure by force if necessary.

Theater? Banned—too frivolous. Dancing? Banned—leads to lust. Drinking? Heavily restricted. Colorful clothing? Discouraged. Basically anything fun was suspicious.

And Christmas? Oh, Christmas was the worst offender of all.

Why Puritans Hated Christmas

From a Puritan perspective, Christmas was basically everything wrong with religion and society rolled into one terrible holiday.

First, the theological problems. Puritans pointed out—correctly—that the Bible never commands Christians to celebrate Jesus’ birth on December 25th. There’s no biblical evidence that’s actually when he was born. The date was chosen centuries after Christ, probably to coincide with pagan winter solstice festivals.

So right there, Christmas was a man-made tradition, not divinely ordained. And Puritans were very concerned about not adding human traditions to what God actually commanded. If the Bible doesn’t say to do it, you probably shouldn’t.

Second, the historical corruption. Christmas had absorbed elements from pagan winter festivals—evergreen decorations, feasting, gift-giving, the whole aesthetic. To Puritans, this was syncretism—blending Christianity with paganism. Exactly what they’d spent centuries trying to purge from the church.

Third—and this was the big one—Christmas had become associated with excess. The traditional way to celebrate Christmas in 17th-century England involved:

- Massive feasting (we’re talking days of overeating)

- Heavy drinking (people got thoroughly drunk)

- Gambling and games

- Cross-dressing and role reversals (servants ordering masters around)

- General revelry and disorder

Basically, Christmas was a sanctioned period of controlled chaos. Social norms relaxed. People indulged. The whole thing resembled the Roman Saturnalia more than anything Christian.

To Puritans, this was horrifying. Here was a holiday claiming to honor Christ that actually involved gluttony, drunkenness, and behavior that would get you in serious trouble any other time of year. It wasn’t worship—it was idolatry disguised as religion.

So when Puritans gained power, Christmas had to go. Not reformed. Not modified. Abolished.

The Day Christmas Died (Officially)

In 1647, Parliament passed an ordinance officially banning Christmas celebrations.

The announcement was straightforward: December 25th was no longer a holiday. Markets would be open. Work would continue as normal. No church services specifically for Christmas. No festivities. Anyone caught celebrating would face consequences.

The justification was presented as religious reformation. This wasn’t about controlling people—it was about purifying worship, removing man-made traditions, focusing on what God actually commanded rather than what traditions had accumulated.

But to ordinary people, it felt like their government had just stolen Christmas.

Because here’s the thing: Christmas wasn’t just a religious holiday. It was a cultural touchstone, a moment of community gathering, a brief respite in the harsh winter when people could feast and celebrate and forget their troubles for a few days.

It was the one time when social hierarchies relaxed, when servants might sit at table with masters, when the poor could expect generosity from the rich. It was when apprentices got time off, when families gathered, when communities came together.

Taking that away wasn’t just religious reform—it was cultural destruction.

The reaction was immediate and furious.

When England Fought Back

The resistance to the Christmas ban was widespread, creative, and occasionally violent.

In some towns, people straight-up rioted. Canterbury saw particularly serious unrest, with crowds taking to the streets demanding their Christmas back. The mayor who tried to enforce the ban faced angry mobs. Similar scenes played out elsewhere—people refusing to open their shops, forcing their way into churches to hold illegal Christmas services, openly defying the authorities.

But most resistance was quieter and sneakier.

Families held clandestine Christmas gatherings in their homes. You couldn’t have public festivities, but what you did in private was harder to police. So people closed their shutters, lowered their voices, and celebrated anyway. Secret feasts. Forbidden carols. Illegal mince pies.

Yes, mince pies became acts of rebellion. The specific mixture of meat, fruit, and spices traditionally eaten at Christmas? Banned. Making or eating them became a small act of defiance against Puritan overreach.

Churches found workarounds. If you couldn’t hold a Christmas service on December 25th, maybe you could hold a regular service that just happened to focus on Christ’s nativity. Technically not celebrating Christmas. Just coincidentally preaching about it.

Communities developed coded language and symbols. Ways to signal that you were celebrating without explicitly admitting it. Underground networks of resistance to preserve traditions the government wanted dead.

The black market flourished. If Christmas foods were banned, people would pay extra for them. Enterprising individuals risked punishment to provide Christmas goods to people desperate to maintain some normalcy.

This wasn’t just about stubbornness or loving parties. For many people, the Christmas ban represented tyranny—government overreach into the most personal and cultural aspects of their lives. If they could ban Christmas, what couldn’t they ban?

Regional Rebellion

The interesting thing about Christmas resistance is how it varied by region.

In London and areas with strong Puritan presence, enforcement was stricter and compliance—however grudging—was higher. People might grumble, but the combination of ideological support for the ban and strong enforcement meant celebrations were suppressed.

But in rural areas, or regions where Puritanism had less influence? Good luck enforcing that ban.

Yorkshire villagers kept celebrating like nothing had changed. The government could pass all the ordinances it wanted—they were still having their Christmas feast, thank you very much. When authorities tried to intervene, they faced communities closing ranks, nobody seeing anything, nothing to report here officer.

The West Country similarly maintained traditions. These were areas where Christmas was deeply embedded in local identity, where the rhythms of the agricultural year made that winter celebration crucial, where Puritan theology had never gained the same foothold.

So you had a bifurcated England. Urban, Puritan-influenced areas grudgingly (or enthusiastically) abandoning Christmas. Rural, traditional areas carrying on and daring anyone to stop them.

This regional variation reveals that the “Christmas ban” was never as absolute as the ordinances suggested. It was enforced where authorities had power and will to enforce it, ignored where they didn’t.

Which meant that the Puritan vision of a unified, reformed England was always somewhat fictional. Cultural traditions were too strong, local identities too powerful, to be erased by parliamentary decree.

The Artists Strike Back

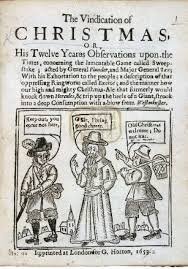

While people resisted through action, writers and artists resisted through creation.

Poets wrote verses celebrating Christmas, often coded to avoid direct confrontation but clear in their meaning. Robert Herrick’s Christmas poems mourned the lost festivities while celebrating their memory, keeping the traditions alive in literature even when suppressed in practice.

These weren’t just nostalgic reminiscences. They were political acts. Publishing poetry celebrating banned festivities was a form of dissent, a way of saying: you can pass laws, but you can’t kill culture.

Artists incorporated Christmas imagery into their work, subtle enough to avoid censorship but recognizable to those who knew what to look for. Visual reminders that the traditions persisted even underground.

Pamphlets circulated—some anonymously—arguing against the Christmas ban. They made theological arguments (actually, celebrating Christ’s birth is good), practical arguments (people need holidays), and political arguments (the government has no right to ban cultural traditions).

This literary and artistic resistance served multiple purposes. It preserved knowledge of Christmas traditions for future generations. It provided rallying points for resistance. It demonstrated that culture couldn’t be simply legislated away.

And crucially, it documented the absurdity and unpopularity of the ban. These works ensured that history would remember not just that Christmas was banned, but that people hated it and fought back however they could.

The Glorious Return

When the monarchy was restored in 1660 and Charles II took the throne, one of the first things people did was bring back Christmas.

Not officially—there was no grand proclamation restoring the holiday. It just… came back. People started celebrating openly again. Churches held Christmas services. Markets closed on December 25th. The feasting and merriment resumed.

Because here’s what Cromwell and the Puritans never understood: you can’t kill a tradition by banning it if the tradition meets genuine human needs.

Christmas provided community gathering in the dark winter. It offered hope and celebration during the hardest time of year. It created space for generosity, for social bonds, for brief escape from hierarchies and hardship.

Those needs didn’t disappear when Parliament passed ordinances. They just went underground, waiting for the opportunity to resurface.

The Restoration allowed that resurfacing. And the Christmas that emerged had been shaped by its time in exile. Some traditions had evolved. New elements had been added. The experience of suppression had actually strengthened people’s attachment to the holiday.

In some ways, the ban backfired spectacularly. By making Christmas illegal, Puritans turned it into an act of resistance. They politicized what had been cultural tradition. They made celebrating Christmas a statement about freedom, about resisting tyranny, about maintaining identity against oppression.

Post-Restoration Christmas carried that weight. It wasn’t just a holiday—it was a symbol of what had been lost and regained, of cultural resilience, of the limits of government power over people’s lives.

The Parallel Universe Where This Worked

It’s worth noting that Puritan suppression of Christmas did work in some places.

In New England, Puritan colonists successfully banned Christmas for decades. The Massachusetts Bay Colony made it illegal to celebrate, and that ban stuck for a long time. No riots. No widespread resistance. Just… compliance.

Why the difference? Several factors:

The New England Puritans were self-selected—people who chose to immigrate specifically for religious reasons. They were ideologically committed in ways the general English population wasn’t.

The colonies were newer, with less entrenched cultural tradition around Christmas. You can’t have nostalgia for traditions that weren’t established yet.

The social control mechanisms were different—smaller, tighter communities where enforcement was easier and social pressure more intense.

And crucially, there was nowhere else to go. In England, you could move to a less Puritan region. In Massachusetts, you were stuck.

So the same Puritan ideology that failed to suppress Christmas in England succeeded in New England. Context mattered enormously.

This tells us something important: cultural traditions persist when they’re deeply rooted, widely shared, and meet genuine needs. They can be suppressed in specific contexts with the right combination of ideology, social control, and lack of alternatives. But in diverse, complex societies with deep cultural roots? Much harder.

What This Tells Us About Now

The Cromwell Christmas ban feels like ancient history, but it’s weirdly relevant to contemporary debates.

We’re constantly arguing about which traditions should be preserved or abandoned, who gets to decide what holidays mean, whether cultural practices should adapt to ideological preferences.

Should corporations say “Merry Christmas” or “Happy Holidays”? Should public spaces display religious symbols? How do we balance inclusive language with traditional celebration? Can you separate cultural Christmas from religious Christmas?

These questions echo the Puritan dilemma: how do you handle traditions that mean different things to different people, that mix sacred and secular, that don’t fit neat ideological categories?

The Christmas ban also illustrates the limits of top-down cultural engineering. The Puritans were sure they were right—theologically, morally, practically. They had power. They passed laws. They enforced them.

And they failed. Because culture doesn’t work that way. You can’t simply decree traditions away, especially traditions that serve genuine human needs and are embedded in collective identity.

This doesn’t mean traditions never change—they obviously do. But they change organically, through social negotiation, as people adapt practices to new contexts. Not through governmental fiat.

The story also reveals the tension between religious conviction and popular will. The Puritans genuinely believed Christmas was corrupted and needed abolition. They weren’t just being mean—they thought they were saving souls.

But good intentions don’t eliminate the problem of imposing your religious beliefs on people who don’t share them. The Christmas ban was theocratic overreach, even if motivated by sincere faith.

That tension persists today in different forms. How much should government reflect religious values? When does religious freedom become religious imposition? Where’s the line between maintaining moral standards and enforcing private beliefs?

The Festival That Wouldn’t Die

So what’s the lesson from Christmas under Cromwell?

That cultural traditions have power and resilience beyond what laws can suppress. That human needs for celebration, community, and joy persist regardless of what authorities decree. That trying to impose ideological purity on messy human culture is a fool’s errand.

The Puritans saw Christmas as corrupted by excess and needed to be abolished. What they didn’t understand was that the “excess” was precisely the point—the release, the celebration, the brief escape from normal constraints.

People don’t just celebrate holidays because they’re supposed to. They celebrate because they need to. Because winter is dark and hard, and gathering with community to feast and make merry makes it bearable. Because life is difficult, and moments of joy matter.

You can’t legislate away that need. You can suppress its expression temporarily, but it will find a way back. Like water flowing downhill, the human impulse to celebrate will route around obstacles.

The fact that Christmas survived the Puritan ban—and arguably came back stronger—demonstrates this resilience. The holiday evolved, adapted, absorbed the experience of suppression, and persisted.

That’s what culture does. It bends but doesn’t break. It goes underground but doesn’t disappear. It waits for its moment, then resurfaces.

The Ghost of Christmas Past

Today, Christmas faces different challenges than Puritan suppression. Not governmental bans, but commercial exploitation. Not theological objections, but cultural wars about inclusivity and secularization.

Some people worry Christmas is too religious, excluding non-Christians. Others worry it’s not religious enough, buried under consumerism and secular symbols. Some think it’s too commercial. Others think the religious origins should be completely stripped.

It’s the Cromwell debate in a different key—arguments about what Christmas should be, who gets to define it, which traditions are worth preserving.

But the lesson from the 1640s still applies: Christmas will be whatever people make it. Authorities—religious, governmental, or commercial—can influence it, but they can’t control it.

The holiday has survived Puritan suppression, Victorian sentimentalization, commercial exploitation, and cultural battles about its meaning. It persists because it continues to meet needs—for community, for celebration, for marking the year’s rhythm, for creating meaning in winter’s darkness.

Those needs transcend any particular expression of the holiday. Which is why Christmas keeps evolving while fundamentally staying the same.

The Ending Cromwell Wouldn’t Have Wanted

So that’s the story: Puritans banned Christmas, people rebelled, traditions survived underground, the holiday came roaring back when suppression ended.

Oliver Cromwell probably thought he was doing the right thing—purifying religion, reforming society, saving souls from the sin of excessive celebration. In his mind, the Christmas ban was moral leadership.

In reality, it was a spectacular demonstration that you can’t kill culture by decree. That traditions rooted in genuine human needs will persist. That people will resist when authorities try to control the most personal and meaningful aspects of their lives.

The Christmas that came back after Restoration wasn’t quite the same as what existed before. It had been shaped by suppression, strengthened by resistance, made more precious by its temporary loss.

Every tradition that survives attack becomes more powerful. Every cultural practice that persists despite suppression carries the weight of that persistence.

Modern Christmas—in all its messy, commercialized, contested glory—owes something to those English people who secretly baked mince pies, gathered in shuttered homes to sing banned carols, and refused to let their government tell them they couldn’t celebrate the way their families had for generations.

They didn’t think of themselves as heroes or cultural warriors. They just wanted their Christmas back.

And they got it. Because ultimately, that’s what happens when tradition meets tyranny.

The tradition wins.

Merry Christmas, Oliver Cromwell. You tried to cancel the holiday and only made it stronger.

That’s the most Christmas miracle of all.