The Monk Who Brought Orthodox Christianity to a Scottish Island

Orthodox Christianity on a Scottish island monastery

Orthodox Christianity on a Scottish island may seem unlikely, but the story of one monk’s perseverance reveals how ancient faith traditions can take root in unexpected places.

When East Met West on Holy Ground

The Isle of Iona sits off the west coast of Scotland—a tiny island, barely three miles long, wind-swept and beautiful and soaked in Christian history.

This is where Saint Columba established his monastery in 563 AD. Where Celtic Christianity took root and spread across Scotland. Where Scottish kings were buried. Where pilgrims have journeyed for fourteen centuries seeking God.

It’s also, historically, not Orthodox. At all.

Celtic Christianity predates the East-West schism. When Iona’s monastery was thriving, Orthodox and Catholic were still one church. By the time they split in 1054, Scotland was firmly in the Western, Catholic camp. After the Reformation, it became Presbyterian.

Orthodox Christianity—with its Byzantine liturgy, icon veneration, and Eastern theology—had exactly zero historical presence on Iona.

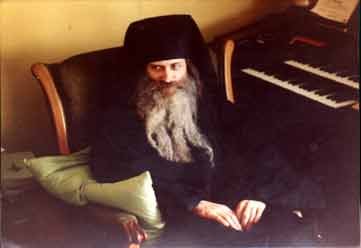

Until 1973, when Father Seraphim arrived.

A Russian Orthodox monk. Coming to a Scottish island. To establish Orthodox Christianity. On ground sacred to Celtic and Presbyterian traditions.

This should have been a disaster. Cultural mismatch. Theological confusion. Local resistance to an Eastern import on Western holy ground.

Instead, Father Seraphim built something remarkable: a thriving Orthodox community on Iona that honors the island’s Celtic heritage while introducing ancient Eastern Christian practices. A pilgrimage destination drawing visitors from across the globe. A spiritual sanctuary that somehow bridges East and West, ancient and modern, Scottish and Slavic.

This is the story of how an Orthodox monk brought Byzantine Christianity to a Celtic island and made it not just work, but flourish.

It’s also a story about what makes a place sacred, whether religious traditions can cross cultural boundaries authentically, and how sometimes the most unlikely combinations create something beautiful.

Welcome to Iona, where Russian chant echoes off Celtic stones and pilgrims discover that holy ground transcends the boundaries we draw on maps.

The Island That Christianity Built

Before we talk about Father Seraphim, we need to understand Iona—because this island’s spiritual significance predates any modern Christian denomination.

In 563 AD, Saint Columba—Irish monk, missionary, possibly fleeing penance for a war he helped start—arrived on Iona with twelve companions. He established a monastery. From this tiny island, Celtic Christianity spread across Scotland and northern England.

The monastery became a center of learning, art, and spiritual power. The Book of Kells was likely created here. Scottish kings were buried here—over forty of them, including Macbeth (yes, that Macbeth). Pilgrims journeyed here for centuries.

Then Vikings destroyed the monastery in the 9th century. It was rebuilt, destroyed again, rebuilt again. By the Reformation, Iona’s glory days seemed over. The abbey fell into ruins.

But the island never lost its spiritual magnetism. Something about this place—the light, the landscape, the history soaked into the stones—kept drawing people seeking God.

In the 1930s, George MacLeod founded the Iona Community, restoring the abbey and creating an ecumenical Christian community focused on peace, justice, and spiritual renewal. By the 1970s, Iona was again a pilgrimage destination, though primarily Protestant in character.

This is the Iona that Father Seraphim encountered: ancient, sacred, beautiful, and thoroughly Western Christian in identity.

Bringing Eastern Orthodoxy here wasn’t obvious or easy. It was audacious.

The Monk Who Saw Possibility

Father Seraphim wasn’t Scottish. He wasn’t Celtic. He came from the Russian Orthodox tradition—a completely different Christian world from Presbyterian Scotland.

But he was called to Iona. Not just geographically, but spiritually. He felt God directing him to this specific island to establish Orthodox Christianity.

Why Iona? What made this particular place the right location for an Orthodox presence?

The island’s existing spiritual significance. Iona was already holy ground. Already a pilgrimage site. Already recognized as a place where heaven and earth feel closer. Father Seraphim wasn’t imposing sacredness on secular space—he was adding to existing sanctity.

The Celtic-Orthodox connection. While Celtic Christianity developed independently from Eastern Orthodoxy, there are similarities: emphasis on creation spirituality, monastic tradition, mystical approach to faith, use of spiritual practices like prayer and fasting. Father Seraphim recognized kinship between Celtic and Orthodox spirituality.

The island’s openness to pilgrimage. Iona already welcomed spiritual seekers. Father Seraphim wasn’t fighting against a closed community—he was joining a tradition of diverse Christians coming to this sacred space.

The isolation that allows focus. Islands create natural retreat from daily life. The journey to Iona requires intentionality—you can’t stumble onto it accidentally. This makes it perfect for serious spiritual pilgrimage.

Still, arriving in 1973 with plans to establish Orthodox Christianity on a Presbyterian Scottish island took either profound faith or significant delusion. Possibly both.

The Skeptical Welcome

When Father Seraphim arrived, the local reaction was… complicated.

Curiosity: Who is this Russian monk? What’s he doing here? What even is Orthodox Christianity?

Skepticism: Is this legitimate or some weird fringe thing? Does Iona need another Christian tradition when we already have several?

Concern: Will this disrupt the island’s existing spiritual community? Will it create conflict or confusion?

Caution: We don’t really know this guy. Should we trust someone bringing an unfamiliar religious tradition?

These reactions were reasonable. Communities have the right to be protective of their sacred spaces and skeptical of newcomers claiming religious authority.

Father Seraphim couldn’t just show up and demand acceptance. He had to earn trust, demonstrate authenticity, prove that Orthodox Christianity could honor rather than compete with Iona’s existing spiritual heritage.

He did this through:

Humility: Not claiming to replace or supersede existing traditions, but offering another expression of ancient Christian faith.

Respect for Celtic heritage: Studying Saint Columba, honoring Iona’s history, finding connections between Celtic and Orthodox spirituality rather than emphasizing differences.

Service: Contributing to island life beyond just religious services. Being a good neighbor and community member.

Authentic practice: Living Orthodox Christianity genuinely rather than performing it for show. Daily prayer, fasting, discipline—the real monastic life, not a tourist attraction.

Patience: Not demanding immediate acceptance, but letting relationships develop organically over time.

Gradually, skepticism softened. Not everyone embraced Orthodox Christianity, but most recognized Father Seraphim’s sincerity and valued his presence.

Building Something New from Something Ancient

Father Seraphim didn’t try to replicate a Russian monastery on Scottish soil. He created something hybrid—deeply Orthodox in theology and practice, but adapted to Iona’s unique context.

The liturgy: Byzantine Divine Liturgy, but sometimes incorporating Celtic elements. Chanting in Slavonic and English. Icons alongside Celtic crosses.

The community: Small, intentionally so. Not trying to convert all of Iona, but creating a faithful Orthodox presence.

The schedule: Daily prayer following Orthodox tradition. Fasting periods. Feast days. The rhythm of the liturgical calendar organizing time.

The hospitality: Welcoming pilgrims regardless of their tradition. You didn’t have to be Orthodox to attend services or participate in community life.

The teaching: Explaining Orthodox Christianity to people unfamiliar with it. Not assuming knowledge, but educating gently about icons, liturgy, theology, spiritual practices.

What emerged was Orthodox Christianity that honored its Eastern roots while being contextualized for a Western setting. Not diluted—the theology and practice remained authentically Orthodox. But adapted for people whose Christian experience was Presbyterian, Catholic, Anglican, or no tradition at all.

The Pilgrims Who Came

Word spread. An Orthodox community on Iona. Byzantine liturgy on Celtic holy ground. A monk offering spiritual guidance in a place already known for sanctity.

Pilgrims started arriving:

Orthodox Christians from elsewhere, seeking authentic Orthodox worship in an unexpectedly beautiful setting. Russians, Greeks, Middle Easterners discovering Iona through Father Seraphim’s presence.

Western Christians curious about Orthodoxy, drawn by the mystical elements, the liturgical beauty, the ancient practices they’d never encountered in their home churches.

Spiritual seekers without clear tradition, looking for depth, mystery, connection to something transcendent. Finding in Orthodox liturgy what their contemporary Christianity lacked.

People seeking retreat and renewal, regardless of specific theological interest. Drawn by Iona’s beauty and peace, staying for Father Seraphim’s spiritual wisdom.

The pilgrimages grew. Not massive—Iona’s small, and Father Seraphim wasn’t trying to build a mega-monastery. But steady. Significant. People intentionally traveling to this island specifically to experience Orthodox Christianity in this unique context.

They came for:

The Divine Liturgy: Experiencing worship that’s remained essentially unchanged for over a millennium. The chanting, incense, icons, mystery.

Spiritual direction: Father Seraphim offering guidance, hearing confessions, counseling people through spiritual struggles.

The rhythm of monastic life: Praying the hours, participating in the daily cycle of worship, experiencing time organized by prayer rather than productivity.

The combination of Iona’s beauty and Orthodox practice: Natural beauty as context for liturgical beauty. Scottish landscape meeting Byzantine spirituality.

Community with other pilgrims: Shared meals, conversations, the fellowship of people on similar spiritual journeys.

The Testimonies That Validate the Work

Pilgrims’ accounts reveal what Father Seraphim’s presence on Iona actually accomplished:

Anna from Scotland: “I’d been Presbyterian my whole life. I thought I knew Christianity. Then I attended Divine Liturgy with Father Seraphim. The beauty, the reverence, the sense of participating in something ancient and holy—it transformed my understanding of worship. I’m still Presbyterian, but I’m a different kind of Presbyterian now, enriched by what Orthodoxy showed me.”

Michael from the United States: “I was spiritually adrift. My American evangelicalism felt shallow, performance-oriented, disconnected from history. On Iona, Father Seraphim introduced me to a Christianity that’s two thousand years deep. The icons, the liturgy, the theology—it’s like discovering Christianity for the first time. I eventually converted to Orthodoxy, and it started on that island.”

Dmitri from Russia: “Finding Orthodox worship on a Scottish island was surreal. But Father Seraphim created something authentically Orthodox while honoring Iona’s Celtic heritage. It wasn’t Russian Orthodoxy transplanted—it was universal Orthodoxy expressed in a new context. That’s powerful.”

Sarah, no denominational affiliation: “I wasn’t Christian when I came to Iona. I was just searching. Father Seraphim didn’t push conversion. He offered hospitality, answered my questions, let me participate in services without pressure. The experience opened me to Christianity in ways aggressive evangelism never could.”

These testimonies share common themes:

Depth: Orthodox Christianity offering theological and liturgical depth many felt was lacking in Western Christianity.

Beauty: The aesthetic dimension of worship—icons, chant, incense, liturgy—as pathway to encountering God.

Ancientness: Connection to early Christianity, to practices unchanged for centuries, to roots that feel more solid than contemporary innovations.

Mystery: Embracing rather than explaining away the inexplicable elements of faith. God as ultimately unknowable even while intimately present.

Hospitality: Father Seraphim welcoming everyone regardless of tradition or certainty, creating space for authentic seeking.

The Cultural Bridge Nobody Expected

Here’s what’s remarkable: Father Seraphim created authentic cultural exchange, not cultural erasure or dominance.

He didn’t try to make Iona Russian. He didn’t demand Scottish converts abandon their heritage for Slavic Orthodoxy.

He also didn’t water down Orthodox Christianity to make it more palatable to Western sensibilities. The theology remained Orthodox. The liturgy stayed Byzantine.

What he created was mutual enrichment:

Orthodox Christianity gaining Celtic context: Recognizing how Celtic spirituality and Orthodox mysticism share certain sensibilities. Finding connections between Saint Columba and the Desert Fathers.

Iona’s heritage gaining Orthodox depth: The island’s ancient Christianity being understood through Orthodox lens, revealing theological richness that Protestant interpretation sometimes missed.

Scottish pilgrims encountering Eastern Christianity: Breaking the assumption that Christianity is monolithic, discovering diverse expressions of one faith.

Orthodox pilgrims experiencing Celtic holy ground: Recognizing that sanctity transcends jurisdictional boundaries, that God meets people in diverse contexts.

This is rare. Usually, religious cross-cultural exchange goes poorly:

Either: Dominant culture imposes its version, erasing local expression (colonialism).

Or: Traditions stay completely separate, missing opportunities for genuine dialogue and mutual learning.

Father Seraphim achieved something different: respectful integration that honors both traditions while creating something new.

The Modern Pilgrimage Experience

Today, Iona remains a thriving pilgrimage destination, and Father Seraphim’s Orthodox presence is an established part of that landscape.

The island offers:

Daily Orthodox worship: Divine Liturgy, prayer hours, feasts and fasts according to the liturgical calendar.

Retreat opportunities: Structured programs for spiritual formation, silent retreats, guided prayer experiences.

Accommodations: Ranging from simple monastic cells to more comfortable guesthouses. Options for different pilgrimage styles.

Spiritual direction: Ongoing availability of monks and spiritual guides for confession, counsel, and prayer.

Community meals: Shared eating as part of the pilgrimage experience, breaking bread with fellow seekers.

Access to Iona’s beauty: Time to walk the island, pray outdoors, experience creation as part of spiritual practice.

The experience adapts to modern needs while preserving ancient practices:

Technology boundaries: Limited Wi-Fi, encouraging disconnection from constant digital stimulation.

Accessibility considerations: Making pilgrimage possible for people with physical limitations, though the island’s terrain presents natural challenges.

Diverse scheduling: Options for people who can stay weeks and people who can only manage days.

Ecumenical welcome: Orthodox services remain Orthodox, but visitors from any tradition (or none) are welcomed to participate as they’re comfortable.

This isn’t religious tourism—though tourism exists alongside pilgrimage. This is authentic spiritual practice made available to contemporary seekers in forms that remain faithful to ancient tradition.

The Legacy That Outlasts One Monk

Father Seraphim’s contribution wasn’t just establishing Orthodox presence on Iona. It was demonstrating that:

Sacred space transcends denominational boundaries. Iona can hold Celtic, Presbyterian, Orthodox, Catholic, Anglican expressions of Christianity without any diminishing the others.

Ancient practices remain vital. Byzantine liturgy dating from the first millennium still speaks powerfully to 21st-century seekers.

Cultural adaptation doesn’t require cultural erasure. Orthodox Christianity can be authentically Orthodox while being contextualized for Scottish settings.

Pilgrimage meets deep human needs. The intentional journey to sacred space for spiritual renewal is as relevant now as in medieval times.

Beauty is theological. Icons, chant, incense, liturgy—these aren’t decorations but pathways to encountering divine beauty.

Community sustains faith. Shared prayer, meals, life together—these create and maintain spiritual vitality.

His legacy continues through:

The ongoing Orthodox community on Iona, maintaining the liturgical and monastic life he established.

The pilgrims who return annually, for whom Iona has become essential to their spiritual rhythm.

The people who converted to Orthodoxy after encountering it on Iona, now practicing in their home communities.

The cross-cultural dialogue he modeled, showing how traditions can engage respectfully and enrich each other.

The thousands who encountered Orthodox Christianity for the first time through his ministry, expanding their understanding of Christian diversity.

The Uncomfortable Questions

Father Seraphim’s success raises questions worth sitting with:

Is Orthodox Christianity on Iona authentic or appropriative? Is this genuine expression of universal Christianity, or cultural borrowing that doesn’t fully belong?

Does adding another tradition to Iona create richness or confusion? When is religious diversity enriching and when is it just cluttered?

Who has the right to establish religious presence on sacred ground? Should there be gatekeeping around holy places, or should they welcome all legitimate spiritual expression?

Is this sustainable long-term? Can Iona’s Orthodox community continue after its founder passes? Does the work outlast the charismatic leader who started it?

What’s lost when Eastern Christianity gets Westernized (even respectfully)? Does contextualizing Orthodox practice for Scottish pilgrims dilute something essential?

These questions don’t have simple answers. They’re tensions to hold rather than problems to solve.

The Ending That’s Not an Ending

Father Seraphim brought Orthodox Christianity to the Isle of Iona. An Eastern tradition on Western holy ground. Russian liturgy on Scottish stones. Byzantine theology in Celtic context.

It shouldn’t have worked. Cultural mismatch. Historical discontinuity. Potential for conflict or confusion.

But it did work. It works still.

Because Father Seraphim understood something crucial: Sacredness isn’t proprietary.

Iona doesn’t belong exclusively to Celtic Christianity or Presbyterian heritage. It belongs to God and to anyone God calls there.

Orthodox Christianity isn’t limited to Eastern Europe or the Middle East. It’s a universal expression of ancient faith that can take root wherever people genuinely practice it.

Pilgrimage isn’t about reinforcing familiar traditions. It’s about encountering God in new contexts, being transformed by sacred space, discovering depths of faith you didn’t know existed.

Father Seraphim didn’t colonize Iona. He didn’t erase its heritage. He didn’t compete with existing traditions.

He added. He enriched. He created space for another expression of Christianity on ground already recognized as holy.

And thousands have been blessed by it.

The Divine Liturgy still echoes across Iona. Incense still rises alongside Celtic crosses. Icons still reflect light off ancient stones.

Pilgrims still come—Orthodox and not, certain and seeking, from across the globe and from down the road.

They come because something about this place—this unlikely fusion of East and West, ancient and modern, Celtic and Slavic—speaks truth about God that transcends our categories.

They come because Father Seraphim showed that sacred space can hold more than we think, that traditions can coexist and enrich rather than compete, that beauty and depth and ancient practice still matter desperately to contemporary souls.

The Isle of Iona: where Saint Columba planted Celtic Christianity fourteen centuries ago.

Where Father Seraphim planted Orthodox Christianity five decades ago.

Where pilgrims discover that the boundaries we draw between Christian traditions matter less than the God who transcends them all.

Where heaven still touches earth, regardless of whether you’re chanting in Gaelic, Slavonic, or English.

Where the journey continues.

One pilgrim at a time.

One prayer at a time.

One Divine Liturgy echoing across the stones.

Orthodox Christianity on a Scottish island.

It works.

Because holiness doesn’t respect the borders we draw.

It just is.

And Father Seraphim had the wisdom to recognize it.