The Emperor Who Saw God: How One Vision Rewrote Western Civilization

Constantine

When Rome Was Burning (Figuratively)

The Roman Empire in the early fourth century was a dumpster fire wrapped in purple silk.

The Tetrarchy—Diocletian’s brilliant plan to split the empire into manageable chunks—had predictably devolved into exactly what happens when you give four ambitious men competing power bases: civil war. Claimants to the throne were popping up like mushrooms after rain, each convinced they were destined to reunite the fractured empire under their rule.

Meanwhile, in the streets and hidden meeting places across the empire, a strange new religion was spreading. Christianity—that peculiar Jewish sect that worshipped a executed criminal as God—had somehow survived three centuries of intermittent persecution. Despite being illegal, socially unacceptable, and occasionally lethal to practice, it kept growing. Something about a message of universal love, forgiveness, and eternal life resonated with people living under the boot of imperial power.

The pagans—which is to say, nearly everyone who mattered politically—viewed Christians with a mixture of contempt and confusion. These people refused to honor the emperor as divine. They wouldn’t participate in traditional sacrifices. They had bizarre ideas about the afterlife and morality. They were, from the Roman establishment’s perspective, dangerously subversive.

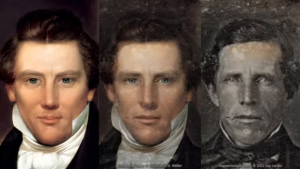

Into this powder keg of political chaos and religious tension walked Constantine, son of a minor emperor, ambitious beyond measure, and about to have an experience that would change the course of human history.

He had no idea that a single vision would transform him from just another power-hungry warlord into the man who would make Christianity the dominant force in Western civilization.

The Night Before Everything Changed

October 27, 312 AD. Constantine’s army was camped outside Rome, preparing for what might be a suicidal assault.

Across the Tiber River, his rival Maxentius held the city with superior numbers and defensive advantages. Militarily, Constantine was probably screwed. He’d marched into Italy on ambition and momentum, winning a few battles along the way, but now he faced the big test. Lose here, and it was game over—not just politically, but probably literally. Roman civil wars didn’t end with gentlemanly concessions.

Constantine needed an edge. Something to inspire his troops. Some sign that the gods favored his cause.

And then, if we believe the accounts, he got one.

The story varies depending on who’s telling it. In some versions, Constantine saw a cross of light in the sky above the sun, with words proclaiming “In this sign, conquer.” In others, he had a dream that night where Christ himself appeared and told him to mark his soldiers’ shields with a Christian symbol.

Skeptics have spent centuries debating what actually happened. Was it a genuine religious experience? A calculated fabrication? A convenient story invented after the fact to legitimize his conversion? A meteorological phenomenon interpreted through religious expectation?

Here’s what we know for certain: Constantine claimed to have seen something. And whatever it was—vision, dream, or strategic inspiration—he acted on it.

He ordered his soldiers to paint the Chi-Rho symbol (the first two letters of “Christ” in Greek) on their shields. This was radical. Christianity was still technically illegal. His troops were traditional Romans who’d spent their lives sacrificing to Jupiter and Mars. And here was their commander telling them to march under the banner of an executed Jewish prophet.

But Constantine was betting everything on this vision. His authority. His legitimacy. His life.

Tomorrow would reveal whether he’d made the worst decision of his career or the most brilliant.

The Bridge Where History Pivoted

The Battle of Milvian Bridge should have been a slaughter—with Constantine as the victim.

Maxentius had every advantage: more troops, fortified positions, home-field advantage. He could have stayed behind Rome’s walls and waited for Constantine’s supplies to run out. Instead, for reasons that remain unclear (divine intervention, according to Christian sources; tactical stupidity, according to military historians), he marched out to meet Constantine at the Tiber River.

The battle itself was brutal and decisive. Constantine’s forces drove Maxentius’s army back toward the bridge. In the chaos of retreat, the temporary pontoon bridge collapsed under the weight of fleeing soldiers. Maxentius, weighed down by armor, drowned in the Tiber.

Constantine had won. Against the odds. Under the Christian symbol.

The message was clear—at least to Constantine: the Christian God delivered. Where Jupiter and Mars had been silent, Christ had provided victory. This wasn’t just military success; it was divine endorsement.

For his soldiers, who’d survived a battle they probably shouldn’t have, the Christian symbol suddenly seemed pretty lucky. For Constantine, it was confirmation that he’d chosen the right divine patron. For the Christian community across the empire, who’d been persecuted and marginalized for three centuries, it was the most improbable reversal imaginable.

The persecuted sect now had a champion with the most powerful job in the world: Roman Emperor.

Everything was about to change.

From Persecution to Power

Constantine didn’t immediately convert the empire to Christianity—that would have been political suicide. What he did was more subtle and, ultimately, more effective.

In 313 AD, Constantine and his co-emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan. The language was carefully crafted to sound neutral: religious tolerance for all. Christians could practice freely. Their confiscated property would be returned. They’d have legal protection.

On paper, this benefited everyone. Pagans could keep their temples. Christians could stop hiding. Religious pluralism would strengthen the empire by ending divisive persecutions.

In reality, this was a revolution disguised as tolerance.

Because once Christianity was legal, Constantine didn’t just tolerate it—he actively promoted it. He built churches. Grand, expensive, architecturally stunning churches that announced Christianity’s new status. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. The Lateran Basilica in Rome. These weren’t modest meeting spaces; they were statements of imperial power channeled through Christian symbolism.

He gave the church legal privileges. Christian clergy got tax exemptions. Church courts gained jurisdiction over civil matters. Sunday became a day of rest across the empire—not because Romans had traditionally honored the sun god (though that helped the transition), but because it was the Christian day of worship.

He got involved in church politics, convening the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD to settle theological disputes that were threatening Christian unity. This was unprecedented: the Roman Emperor, traditionally the high priest of pagan religion, now arbitrating disputes about the nature of Christ.

For Christians who’d spent generations meeting in secret, praying in catacombs, watching friends martyred for their faith, this was disorienting. Good disorienting—they weren’t being fed to lions anymore—but weird. They’d gone from persecuted minority to imperially favored religion in a single generation.

The question nobody wanted to ask out loud: what would this cost them?

When Faith Becomes Policy

Constantine’s conversion transformed Christianity, but not necessarily in ways the apostles would have recognized.

Early Christianity had been radically countercultural. Jesus preached about storing treasures in heaven, not earth. About serving rather than being served. About rejecting earthly power in favor of spiritual kingdom. The early church was marked by its refusal to compromise with Roman power structures—which is why Romans kept killing them.

Constantine’s Christianity looked… different.

It had imperial architecture. Political influence. Access to power. Suddenly bishops were advising emperors. Church councils were convened with imperial authority. Christian symbols adorned military standards—the same standards that conquered and subjugated territories across the known world.

The church gained institutional power, hierarchy, wealth, and influence. Which is great if your goal is organizational success. Less great if your goal is maintaining the radical simplicity of the gospel message.

Some Christians celebrated this development. After centuries of persecution, they saw Constantine as God’s instrument, bringing about the prophesied triumph of Christianity. They built him up as “the thirteenth apostle,” a ruler who would shepherd the faith into its rightful place of prominence.

Others had doubts. Voices of dissent—though quieter, because criticizing the emperor’s religion was politically unwise—questioned whether Christianity could maintain its spiritual integrity while entwined with imperial power. Could you really follow a crucified messiah while enjoying imperial patronage? Could the church speak prophetically to power when it was now part of that power structure?

These tensions would define Christianity for the next two millennia. The church would never fully resolve the contradiction between Jesus’s teachings about humility and service, and the church’s institutional exercise of wealth and power.

Constantine didn’t create this tension—but he certainly accelerated it.

Was It Real? The Skeptic’s Question

Let’s address the elephant in the historical record: Did Constantine actually convert?

The honest answer is: we don’t really know.

What we know is that he claimed to have had a vision. He promoted Christianity throughout his reign. He was baptized—on his deathbed, which was actually common practice at the time, since baptism was thought to wash away all sins and it seemed strategically wise to wait until you’d finished sinning.

What we also know is that Constantine was an astute politician who understood power. Embracing Christianity offered significant advantages:

Political unity. The empire was fragmenting along cultural, ethnic, and religious lines. A universal religion could provide common identity across diverse populations. Christianity, with its missionary zeal and emphasis on conversion, was perfect for this.

Legitimacy. Constantine had seized power through military force. Divine endorsement—Christian style—gave him authority beyond mere military might. If God wanted him as emperor, who were mortals to object?

Organizational infrastructure. By Constantine’s time, the church had developed impressive administrative networks across the empire. Aligning with Christianity meant tapping into an existing communication and organizational system.

Differentiation from predecessors. Previous emperors had persecuted Christians. By championing them, Constantine distinguished himself, appealing to a growing demographic while also appearing magnanimous.

So was it genuine faith or calculated strategy? The answer is probably: both. Human motivation isn’t binary. Constantine could have genuinely experienced something he interpreted as divine intervention while also recognizing its political utility. He could have been sincerely drawn to Christian theology while also appreciating how it served his imperial ambitions.

The more interesting question isn’t whether his conversion was “real” but what it meant for Christianity that this particular emperor, with these particular ambitions, became its most powerful patron.

The Legacy Nobody Expected

Constantine died in 337 AD, having fundamentally altered the trajectory of Western civilization in ways neither he nor anyone else could have fully anticipated.

Christianity went from persecuted sect to state religion in less than a century after his conversion. Pagan temples were gradually closed or repurposed. Christian orthodoxy became imperial policy. The church became institutionally powerful in ways that would shape European politics for over a thousand years.

The medieval church, with its popes and political influence, traces directly back to Constantine’s integration of Christianity with imperial power. The Crusades, called by popes and fought under Christian banners, reflect Christianity’s transformation from pacifist movement to militant force. The Protestant Reformation was partly a reaction against the institutional church that Constantine’s era had birthed.

Even modern secular governments in the West carry DNA from this moment. The idea that government has moral dimensions, that rulers should be evaluated on ethical grounds, that there’s a higher law than imperial decree—these concepts gained traction as Christianity and governance intertwined.

But the legacy cuts both ways.

The church gained power but arguably lost prophetic edge. It became easier to control people with religion when religion was backed by state power. Dissent became heresy. Theological disputes became matters of imperial law. The radical inclusivity of early Christianity—which welcomed slaves, women, and social outcasts into positions of leadership—gave way to more rigid hierarchies mirroring Roman social structures.

Constantine didn’t set out to create medieval Christendom or spark the Reformation or influence modern political philosophy. He was trying to win a civil war and then maintain power in a fractured empire. But his conversion—genuine, strategic, or some complex mixture of both—became an inflection point that bent history in new directions.

The Questions That Won’t Die

The Constantine story refuses to stay in the past because it raises questions every religious community eventually faces:

What happens when faith gains power? Does it maintain integrity or compromise principles? Can you wield political influence without being corrupted by it? Is institutional success compatible with spiritual authenticity?

Should religion and government be separate or integrated? Constantine made them partners. The results were… mixed. Some argue this betrayed Christianity’s essence. Others say it allowed Christianity to shape civilization for the better. The debate continues.

Can a conversion be both genuine and strategic? Or does strategic benefit automatically make it suspect? What do we do with complex human motivations that don’t fit neat categories?

Does divine endorsement equal political legitimacy? Constantine claimed God wanted him as emperor. Countless leaders since have made similar claims. How do we evaluate such assertions? What are the dangers of too easily conflating divine will with political ambition?

These aren’t just historical curiosities. They’re live questions in modern democracies where politicians invoke faith, where religious institutions wield political influence, where voters must discern genuine conviction from convenient performance.

Constantine’s story doesn’t answer these questions. But it forces us to ask them.

The Emperor and the Cross

So what do we do with Constantine?

We can celebrate him as the emperor who saved Christianity from extinction, whose conversion allowed the faith to flourish and shape Western civilization. Without Constantine, Christianity might have remained a marginal sect, eventually disappearing or becoming a historical footnote.

We can criticize him as the emperor who corrupted Christianity, transforming a radical spiritual movement into an institution of power indistinguishable from the empire it once challenged. With Constantine, Christianity gained the world but arguably lost something essential in the process.

Or—and this feels closer to truth—we can hold both realities simultaneously. Constantine’s conversion was historically pivotal and morally ambiguous. It preserved Christianity and changed it irrevocably. It was divinely inspired and politically calculated. It was the best thing that could have happened to the institutional church and possibly the worst thing that could have happened to the church’s soul.

History is rarely clean. The moments that change everything are messy, driven by imperfect people with mixed motives making decisions whose implications they can’t fully grasp.

Constantine was a military commander who saw something in the sky—or dreamed something, or claimed something, or genuinely experienced something—and decided to bet his empire on it. That decision rippled across centuries, shaping nations, igniting wars, inspiring art, provoking reform, and raising questions we’re still wrestling with.

He made Christianity powerful. Whether he made it better is a question each generation must answer for itself.

But one thing is undeniable: the emperor who saw God at Milvian Bridge changed everything. For better and worse, in ways profound and problematic, Constantine bent history toward Christianity.

And we’re still living in the world he made.