The Christmas Conspiracy Nobody Tells You About: When Santa Claus Was Actually Two Different Dudes Fighting for Your Soul

santa claus

The Lie We All Believed

You think you know Santa Claus. Fat guy, red suit, lives at the North Pole, breaks into houses once a year to leave presents. He sees you when you’re sleeping, knows when you’re awake, has an alarming surveillance operation that would make the NSA jealous, but we’re all cool with it because: presents.

Here’s what nobody told you: “Santa Claus” isn’t one person. He’s a Frankenstein’s monster stitched together from multiple competing Christmas figures who spent centuries basically fighting a culture war over who got to define the holiday.

On one side: St. Nicholas, the actual historical saint who gave secretly to the poor and slapped heretics at church councils. A serious religious figure embodying Christian charity and virtue.

On the other: Kris Kringle, a Germanic folk character who started as the Christ Child but evolved into something more… commercial. More fun. More focused on kids and gifts and magic than on piety and virtue.

These weren’t variations of the same legend. They were rival traditions representing fundamentally different visions of what Christmas should be. Religious versus secular. Sacred versus commercial. European versus American.

The modern Santa Claus is what happened when these traditions collided, merged, and got repackaged by Coca-Cola’s marketing department. And the messy history behind that jolly red suit reveals way more about how we celebrate Christmas—and why—than most people realize.

Buckle up. This gets weird.

When Saints Were Badass

Let’s start with St. Nicholas, because his actual story is way cooler than anything Hallmark has ever produced.

Nicholas of Myra lived in the 4th century in what’s now Turkey. He was born into wealth, orphaned young, and inherited a fortune. Most people in that position would’ve bought a nice villa and lived comfortably. Nicholas looked at his money and thought: “How can I secretly give all this away to people who need it more?”

The most famous story involves three sisters whose father couldn’t afford dowries. In that culture, this meant they’d likely be sold into prostitution or slavery. Nicholas heard about their situation and, under cover of darkness, threw bags of gold through their window. Three separate times. Secretly saving them from a horrific fate.

Why secretly? Because Nicholas wasn’t doing this for recognition or reputation. He was embodying Jesus’ teaching about giving without letting your left hand know what your right hand is doing. Anonymous charity. Generosity without ego.

Other stories are even more dramatic. At the Council of Nicaea—the church meeting that defined core Christian doctrine—Nicholas allegedly got so angry at the heretic Arius that he walked over and slapped him in the face. They temporarily stripped him of his bishop’s office for that one, though he was eventually reinstated.

This is important: St. Nicholas wasn’t a cuddly children’s character. He was a serious Christian figure known for fierce defense of doctrine and radical generosity. When people celebrated St. Nicholas Day (December 6), they were commemorating a saint who embodied religious virtues—charity, piety, justice, righteous anger.

His gift-giving wasn’t about making kids happy. It was about reflecting God’s generosity and caring for the vulnerable. It had weight. Purpose. Theological meaning.

This version of Nicholas spread through Europe, with different cultures adapting the legend to fit their contexts. But the core remained: he was a saint, a religious figure, a model of Christian virtue.

Then things got complicated.

Enter the Christ Child (Sort Of)

Now let’s talk about Kris Kringle, whose origin story is delightfully bizarre.

“Kris Kringle” is an Americanization of “Christkind”—literally “Christ Child” in German. During the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther wanted to move gift-giving from St. Nicholas Day (December 6) to Christmas itself, emphasizing Christ rather than a Catholic saint.

So he promoted the idea that the Christkind—a representation of baby Jesus—brought gifts on Christmas Eve. This figure was often depicted as an angelic child with golden hair, embodying innocence and divine gift-giving.

But here’s where it gets weird: as this tradition migrated and evolved, the Christkind transformed. In German-American communities, “Christkind” became “Kris Kringle,” and the character shifted from angelic child to… something else entirely. Something more secular. More magical. More about wonder and joy than religious symbolism.

By the 19th century in America, Kris Kringle had become a jolly gift-giver disconnected from his Christ Child origins. He wasn’t a saint. He wasn’t even particularly religious. He was a folk character—fun, magical, child-friendly, and increasingly commercial.

This version appealed to a rapidly secularizing American culture. You could celebrate Kris Kringle without needing to be particularly Christian. You could enjoy the magic and gift-giving without worrying about theology or virtue.

St. Nicholas represented Christmas as a religious holy day. Kris Kringle represented Christmas as a cultural celebration. And these two visions were about to collide.

The Culture War You Didn’t Know Happened

Throughout the 19th century, different immigrant communities brought their Christmas traditions to America. Dutch settlers brought Sinterklaas (their version of St. Nicholas). German immigrants brought Kris Kringle. British traditions included Father Christmas. Scandinavian folklore added its own elements.

Each tradition emphasized different aspects. Some were more religious, some more secular. Some focused on children, others on community. Some involved gift-giving, others emphasized feasting or charity.

These weren’t just competing traditions—they represented competing visions of what Christmas should be. The religious faction wanted Christmas to remain focused on Jesus’ birth, with any gift-giving reflecting Christian charity. The secular faction wanted a holiday about family, joy, and celebration, with religious elements optional.

In this environment, St. Nicholas and Kris Kringle weren’t just two names for the same character. They were rival figures representing different camps in this cultural negotiation.

St. Nicholas was the choice of religious conservatives who wanted Christmas to maintain sacred meaning. Churches celebrated St. Nicholas Day with services and sermons about charity and virtue. The gift-giving associated with him was supposed to teach Christian values.

Kris Kringle was the choice of folks who wanted Christmas to be fun, magical, and accessible to everyone regardless of religious conviction. He wasn’t weighed down by theology or moral instruction. He was just… nice. Jolly. A source of delight.

The two figures competed for cultural dominance. Which name you used signaled your stance on what Christmas should be. Were you Team St. Nick (religious, traditional, European) or Team Kris Kringle (secular, American, modern)?

Then came the great merger.

When Marketing Created Modern Santa

The modern Santa Claus as we know him emerged gradually through the 19th and early 20th centuries, synthesizing various traditions into one coherent figure.

Key moments in this evolution:

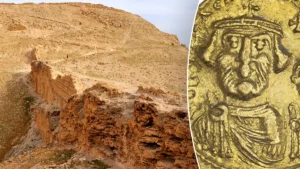

1823: Clement Clarke Moore’s poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (aka “The Night Before Christmas”) created many of Santa’s defining characteristics—the sleigh, the reindeer, the chimney descent, the “jolly old elf” persona. This version drew from multiple traditions, creating something new.

1860s-1880s: Political cartoonist Thomas Nast illustrated Santa repeatedly for Harper’s Weekly, establishing the visual we recognize—rotund figure, fur-trimmed red suit, workshop at the North Pole. Nast’s Santa synthesized St. Nicholas and various folk traditions into one distinctive character.

1890s-1920s: Department stores adopted Santa as a marketing tool, having him appear for photos with children. This commercialized the figure while making him universally accessible. You didn’t need to be particularly religious to visit Santa at Macy’s.

1930s: Coca-Cola’s advertising campaigns featuring Santa (illustrated by Haddon Sundblom) cemented the modern image—always in Coke’s red and white colors, always cheerful, always associated with pleasure and consumption rather than religious virtue.

By mid-20th century, the merger was complete. “Santa Claus,” “St. Nick,” and “Kris Kringle” were all just different names for the same character—a jolly gift-giver who embodied the commercial Christmas spirit.

But what got lost in this synthesis?

The Identity Crisis

Modern Santa Claus is a confused figure because he’s trying to be everything to everyone.

He’s supposed to be St. Nicholas—a model of Christian charity and virtue—but without any explicit religious content that might alienate non-Christian families.

He’s supposed to be magical and whimsical like Kris Kringle, but also moral, keeping lists of naughty and nice children as though he’s a supernatural judge.

He’s supposed to represent generosity and giving, but he’s primarily associated with receiving—kids writing letters demanding toys, sitting on Santa’s lap to request gifts.

He’s supposed to embody the “true spirit of Christmas,” but he’s become capitalism’s mascot, driving billions in retail sales annually.

No wonder the poor guy has an identity crisis.

This confusion stems from trying to merge incompatible traditions. St. Nicholas and Kris Kringle represented different values, different purposes, different visions of Christmas. You can’t just smash them together without creating contradictions.

Religious families still trying to emphasize Christmas’s sacred meaning feel awkward about Santa because he seems to overshadow Jesus. Secular families trying to avoid religious content feel awkward because Santa still carries hints of religious origins and moral judgment.

We’ve created a character who satisfies nobody fully but whom we’re all stuck with because he’s too culturally entrenched to ditch.

What We Actually Believe

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most Americans believe in some version of Santa Claus mythology without examining what that belief implies.

We tell children that Santa is real, that he watches them constantly, judges their behavior, and distributes rewards or withholds them based on a moral calculation. This is… a lot. We’re teaching kids that an invisible, all-knowing figure judges them and that their worth is determined by whether they’ve been “good.”

Some argue this prepares kids for religious concepts—God as judge, cosmic justice, moral accountability. Others argue it’s manipulative, using supernatural threats to control children’s behavior.

We also teach kids that if they’re good, they’ll be rewarded with material goods. That virtue equals presents. That the measure of whether you’re valued is what you receive on Christmas morning.

Then around age 7 or 8, we reveal it was all a lie. Santa’s not real. We made it up. That benevolent figure you believed in? Fiction. The moral system you internalized? Based on falsehood.

What exactly are we teaching here?

Some families handle this well, using the Santa myth as an introduction to symbolism, storytelling, and cultural traditions. Others create lasting trust issues when kids realize they were deliberately deceived about something they took seriously.

The confusion stems from Santa being a hodgepodge of incompatible elements. Is he real? Is he symbolic? Is he just for fun? What’s the point?

St. Nicholas was clear: he was a saint whose life modeled Christian virtue. Kris Kringle was clear: he was a magical folk figure representing holiday joy. Modern Santa? He’s trying to be all of these at once, and it doesn’t quite work.

The Commercialization Problem

Let’s talk about the elephant in the sleigh: Santa Claus is capitalism’s favorite mascot.

Every December, Santa’s image sells everything from cars to credit cards. He’s not promoting charity or generosity—he’s promoting consumption. The “spirit of giving” has morphed into the spirit of buying. Lots and lots of buying.

This is about as far from St. Nicholas’s anonymous, sacrificial charity as you can get. Nicholas gave from his own resources to help people in desperate need. Modern “Santa-inspired” giving is mostly buying toys for kids who already have plenty while retailers post record profits.

The commercialization works because we’ve stripped Christmas figures of their original meaning. St. Nicholas represented Christian values that challenged materialism and selfishness. That version couldn’t sell products. So we transformed him into something else—a magical reward-giver whose primary association is receiving presents.

Religious critics are right to be uncomfortable with this. The modern Santa has become the opposite of what St. Nicholas represented. Instead of teaching selfless generosity, he teaches “I want.” Instead of emphasizing caring for the vulnerable, he emphasizes getting stuff for yourself and your own kids.

Secular critics should be uncomfortable too. We’ve created a mythology that teaches children their value is determined by what they receive, that happiness comes from material goods, that the pinnacle of December is opening presents under a tree.

Neither the religious nor the secular version of Christmas values is well-served by modern Santa.

Can We Fix This Mess?

So what do we do with Santa Claus going forward?

Some families are ditching him entirely, finding his commercialization and deception problematic. They focus on Jesus (if religious) or winter celebrations and family time (if secular), avoiding the Santa mythology.

Others are trying to reclaim Santa by emphasizing his St. Nicholas roots—teaching kids about the real person, his charitable works, his Christian faith. Using Santa as a vehicle for teaching generosity rather than getting.

Still others just roll with it, treating Santa as harmless fun without worrying too much about deeper meaning. For them, Santa’s just part of cultural Christmas, like trees and carols, not requiring deep philosophical justification.

Each approach has merit. The key is being intentional—deciding what you actually want your Christmas celebration to mean, then figuring out whether Santa helps or hinders that goal.

If you want Christmas to be explicitly Christian, modern Santa is probably more hindrance than help. Better to focus on St. Nicholas as a saint, or skip the figure entirely and focus on Jesus.

If you want Christmas to teach genuine generosity and caring for others, modern Santa needs serious renovation. Emphasize giving rather than getting. Connect Santa to service and charity rather than receiving presents.

If you just want fun family traditions without heavy meaning, Santa works fine. Just be honest with yourself and your kids that it’s playful fiction, not something requiring serious belief or moral weight.

The problem is most families don’t think this through. They just do Santa because everyone does Santa, without examining whether it actually serves their values or goals.

The Real History’s Lesson

So what should we take from the real history of Santa Claus?

First: our Christmas traditions are way more constructed and recent than we realize. The modern Santa isn’t ancient folklore—he’s a 19th-century American invention synthesizing various traditions. We created him. We can change him.

Second: the merging of St. Nicholas and Kris Kringle represented a larger cultural negotiation between religious and secular visions of Christmas. That tension hasn’t been resolved—it’s just been papered over with Santa’s jolly image. The discomfort many feel around Santa reflects these unresolved tensions.

Third: commercialization has fundamentally altered what Santa represents. He’s no longer primarily about charity, generosity, or Christian virtue. He’s about consumption, materialism, and retail profits. If that bothers you, you’re not being a killjoy—you’re noticing an actual shift in cultural values.

Fourth: we can be more intentional. Instead of just accepting Santa as given, we can decide what we actually want our Christmas celebrations to mean, then adapt our traditions accordingly. That might mean rehabilitating Santa, or reimagining him, or ditching him entirely.

The choice is ours. Santa doesn’t control Christmas—we do.

The Character We Deserve

Maybe the real issue isn’t Santa himself but what we’ve made him represent.

We’ve taken a historical saint known for radical generosity and a folk character representing childlike wonder, merged them, and turned them into a marketing tool that teaches kids to want more stuff. That’s… kind of dark when you spell it out.

But it doesn’t have to stay that way. Cultural figures evolve because we change them. Santa became commercialized because we let capitalism hijack Christmas. He can become something better if we’re willing to do the work.

That might mean recovering St. Nicholas’s legacy of charitable giving—making Christmas about serving others rather than receiving presents. It might mean emphasizing the wonder and magic that Kris Kringle represented—the joy of childhood, the delight in giving surprise gifts, the pleasure of traditions.

It might mean creating something entirely new—a figure who represents whatever values we actually want to teach during the holidays. We’re not bound by the current version. We made Santa. We can remake him.

Or maybe we just need to be honest: Santa is a confused, contradictory figure because Christmas itself is confused and contradictory. We’re trying to be religious and secular, sacred and commercial, traditional and modern, all at once.

Santa’s identity crisis is our identity crisis. He’s as conflicted as we are about what this holiday actually means.

And maybe acknowledging that is the first step toward figuring it out.

The Ending Nobody Expected

So that’s the real history of Santa Claus: not one jolly figure descended from ancient folklore, but a composite character assembled from competing traditions, commercialized by marketing departments, and now embodying all our contradictions about Christmas.

St. Nick and Kris Kringle weren’t enemies, exactly. They were rival traditions representing different visions of the holiday. And we tried to have both by merging them into Santa Claus—a synthesis that sort of works but never quite resolved the underlying tensions.

Every December, we re-enact this cultural conflict. Religious families uncomfortable with Santa’s secular commercialism. Secular families uncomfortable with his religious origins. Everyone vaguely uncomfortable with the lies we tell children and the consumerism he represents.

We could do better. We could be more intentional about what we actually want Christmas to mean, then create traditions that serve those values rather than just going through motions we’ve inherited.

Or we could just acknowledge that Santa, in all his contradictory glory, is perfectly American—a hodgepodge of immigrant traditions, religious and secular elements, commercialism and idealism, sincerity and cynicism, all wrapped up in a red suit.

Maybe that’s why we can’t give him up. He’s us. Complicated, contradictory, trying to hold incompatible things together, and mostly just hoping the sleigh doesn’t crash.

Merry Christmas. Or Happy Holidays. Or whatever.

Santa’s not judging. He’s too busy having his own identity crisis.