Archaeologists Found Gold in a Desert Monastery (And It Changes Everything We Thought We Knew)

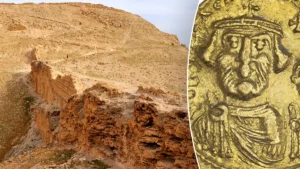

Gold treasure discovered at an ancient Christian monastery in the Judean Desert

Israeli archaeologists recently unearthed ancient gold at a former Christian monastery in the Judean Desert

Archaeologists have uncovered a remarkable gold treasure at an ancient Christian monastery in the Judean Desert, offering new insight into early monastic life, worship practices, and the spiritual history of the region.

When the Desert Gives Up Its Secrets

The Judean Desert keeps secrets well. Harsh, unforgiving, hostile to human life—it’s not the kind of place you expect to hide treasure.

But that’s exactly what it did for over a thousand years.

In 2024, Israeli archaeologists excavating an ancient Christian monastery in the Judean Desert made a discovery that sent shockwaves through the academic world: a cache of gold artifacts. Not just a few coins. A significant treasure trove—jewelry, ceremonial objects, decorative pieces, all crafted from gold and precious stones.

The kind of wealth you don’t expect to find in a remote desert monastery where monks supposedly lived lives of poverty and asceticism.

The discovery raises immediate questions:

How did a monastery in the middle of nowhere accumulate this much wealth? Were these donations from wealthy pilgrims? Payment for spiritual services? Accumulated over centuries? Stolen goods hidden for safekeeping?

Why was it hidden? Was the monastery under threat? Were the monks protecting it from raiders? Was this emergency cache or deliberate storage?

What does this tell us about early Christian monasticism? The narrative is that desert monks fled material wealth to pursue spiritual purity. But this treasure suggests something more complicated—monastic communities integrated into economic networks, accumulating and managing significant wealth.

Who were these monks really? Not isolated ascetics disconnected from the world, apparently. Participants in trade networks. Managers of resources. Possibly quite wealthy.

This isn’t just an exciting archaeological find—it’s a narrative disruptor. It challenges assumptions about early Christian monastic life, about the relationship between spirituality and wealth, about what desert communities were actually doing out there.

This is the story of gold discovered in the last place you’d expect it, and what that discovery reveals about the gap between how we imagine the past and what it actually was.

Welcome to the Judean Desert, where every excavation layer reveals that history is more complicated than the stories we tell ourselves.

The Monastery Nobody Knew Was Rich

Let’s establish what archaeologists thought they knew before finding gold:

The monastery dates to the Byzantine period, roughly 5th-7th century CE. This is when Christian monasticism was flourishing, when hundreds of monks were retreating to the Judean Desert to pursue austere spiritual lives away from the corruptions of urban civilization.

The standard narrative of desert monasticism:

Poverty as spiritual practice. Desert fathers and mothers rejected material wealth. They lived in caves, ate minimal food, owned almost nothing. The desert was where you went to escape the world and its temptations, including money.

Ascetic lifestyle. Prayer, fasting, manual labor sufficient for survival. No luxuries. No accumulation. Just spiritual discipline and communion with God.

Isolation from economic systems. These communities were supposed to be self-sufficient, disconnected from trade networks and commercial activity. Growing their own food, making their own goods, needing little from the outside world.

Focus on spiritual rather than material. The whole point was transcending material concerns. Monks weren’t supposed to care about gold, jewelry, wealth. They cared about prayer, Scripture, salvation.

This narrative is based on actual historical sources—writings from early Christian monastics emphasizing poverty, describing austere lifestyles, condemning wealth and materialism.

But here’s the thing about narratives: They’re often aspirational rather than descriptive. They tell you what people claimed to value, not necessarily what they actually did.

The gold treasure suggests the reality was more complicated.

The Discovery That Didn’t Fit the Script

When the archaeological team started excavating, they weren’t looking for treasure. They were documenting the monastery’s structure, understanding its layout, analyzing how the community functioned.

Then they found gold. Lots of it.

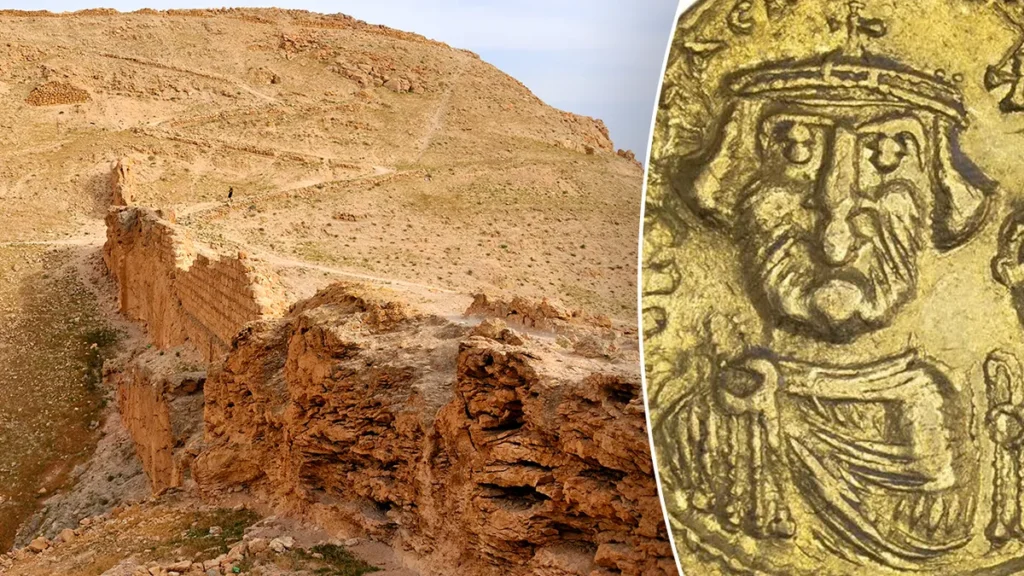

Gold jewelry: Necklaces over 30 centimeters long. Pendants. Brooches. Decorative pieces showing sophisticated craftsmanship.

Precious stones: Garnets, sapphires, other valuable gems incorporated into the jewelry. This isn’t simple metalwork—this is luxury goods.

Ceremonial objects: Gold vessels, possibly for liturgical use. Religious symbols crafted from precious metals.

Weight and value: Several kilograms of gold collectively. In modern terms, hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of precious metal. In ancient terms, massive wealth.

This isn’t a few coins lost by a pilgrim. This isn’t incidental wealth. This is deliberate accumulation of valuable objects by a community that supposedly rejected material possessions.

The immediate reaction from the archaeological team: What the hell?

This doesn’t fit. Desert monasteries are supposed to be poor. Monks are supposed to own nothing. How does an ascetic community accumulate this much wealth?

The Explanations That Don’t Quite Work

Let’s consider the obvious explanations and why they’re insufficient:

“It was donated by wealthy pilgrims.”

Possible. The Judean Desert attracted pilgrims visiting holy sites. Wealthy Christians might have donated to the monastery.

But: If the monastery was committed to poverty, why accept (and keep) such wealth? Why not sell it and give proceeds to the poor? Why accumulate rather than distribute?

“It was hidden during a crisis.”

Also possible. Maybe invaders threatened the monastery. Monks hid the treasure intending to retrieve it later but never could.

But: Why did the monastery have this wealth in the first place? You can only hide what you already possess. Where did it come from?

“It was for liturgical purposes.”

Some items may have been ceremonial—gold vessels for communion, decorative pieces for worship spaces.

But: The quantity suggests more than liturgical necessity. And luxury in worship seems to contradict the ascetic ideal these communities supposedly embodied.

“They were safeguarding it for others.”

Maybe the monastery served as secure storage for wealthy individuals’ valuables.

But: Then it’s not really the monastery’s wealth. And we’d expect better documentation or eventual retrieval. Hidden treasure suggests it belonged to the community.

None of these explanations fully accounts for what was found. Which means the underlying assumptions about desert monasticism might be wrong.

What the Treasure Actually Tells Us

Let’s consider what this discovery reveals about early Christian monastic communities:

They participated in economic networks. You don’t accumulate this much wealth in isolation. The monastery must have been connected to trade routes, to cities, to sources of money and goods.

They managed significant resources. This level of wealth requires management—decisions about what to accept, how to store it, what to do with it. The monastery had economic infrastructure.

Poverty was complicated. Individual monks might own nothing personally while the community collectively controlled wealth. Institutional poverty is different from individual poverty.

Monasteries served multiple functions. Not just spiritual retreat but economic centers, possibly offering services (pilgrimage hospitality, prayer for patrons, education) that generated income.

The ideal and the reality diverged. What monastic writings say about poverty and what monastic communities actually did with wealth weren’t always the same.

This is important because it complicates simplistic narratives about early Christianity. We like stories about pure spiritual communities rejecting worldly concerns. The reality was messier—communities navigating spiritual ideals while operating in economic realities.

The Byzantine Monastery as Economic Institution

Here’s the revised understanding based on this and similar discoveries:

Byzantine-era monasteries weren’t isolated spiritual retreats. They were complex institutions serving multiple functions:

Religious centers: Obviously. Prayer, worship, spiritual formation—the core mission.

Economic hubs: Owning land, managing resources, participating in trade, accumulating wealth from donations and services.

Social service providers: Caring for the poor, sick, travelers. This required resources—you can’t feed the hungry without food and money.

Cultural preservers: Copying manuscripts, maintaining libraries, preserving knowledge. Expensive activities requiring funding.

Political actors: Sometimes wielding influence through their wealth and connections to powerful patrons.

The wealth wasn’t necessarily hypocrisy. It was necessity for fulfilling their broader mission. You can’t run a hospital, library, pilgrimage center, and charity operation without resources.

But it creates tension with the rhetoric of poverty. If monks are supposed to own nothing, how do you justify institutional wealth? Different communities resolved this differently:

Some distinguished between personal and communal property—individual monks own nothing, but the community can possess resources for its mission.

Some emphasized that wealth wasn’t for personal enrichment but for service—it’s okay to manage money if you’re using it for good purposes.

Some probably just lived with the contradiction—claiming to reject wealth while benefiting from it institutionally.

The Judean Desert monastery was navigating these tensions. And the hidden treasure suggests that at some point, the contradiction became untenable—possibly external threat forced them to hide their wealth, revealing its existence.

The Excavation Challenge

Finding treasure sounds exciting. Actually excavating it in the Judean Desert was brutal.

The environment: Extreme heat during the day. You can’t work in midday sun—you’ll collapse. So excavation happened early morning and late afternoon, with breaks during peak heat.

The terrain: Hard sandstone. Densely packed sediment. Removing layers without damaging artifacts requires painstaking work with fine tools—brushes, small trowels, delicate instruments.

Preservation concerns: Gold is stable, but some artifacts had gemstones or other materials that could be damaged by heat, light, or improper handling. Everything had to be removed carefully, documented precisely, preserved immediately.

The uncertainty: Where exactly is the treasure? Geophysical surveys helped identify anomalies in the ground, but ultimately you’re excavating blind until you find something.

The archaeological team worked methodically:

Grid system: Dividing the site into sections, excavating systematically, recording everything found in each location.

Layer by layer: Removing sediment gradually, noting changes in soil composition or artifact density that might indicate different time periods or activities.

Documentation: Photographing, measuring, cataloging every find before moving it. Creating detailed records so the context isn’t lost.

Preservation: Conservation specialists on-site ensuring artifacts are stabilized and protected immediately upon discovery.

This isn’t Indiana Jones. This is slow, methodical, scientific work in difficult conditions. The treasure was hidden for over a thousand years—rushing its excavation would destroy the information it contains.

The Artifacts That Tell Stories

Let’s talk about specific items and what they reveal:

The necklaces: Over 30 centimeters long, intricate filigree work, sophisticated craftsmanship. This wasn’t made locally by monks with basic metalworking skills. This was created by professional artisans in urban centers.

Implication: The monastery had connections to cities, to craft workshops, to trade networks that brought luxury goods to the desert.

The brooches with gemstones: Garnets, sapphires—precious stones that had to be sourced from distant locations and set by skilled jewelers.

Implication: International trade connections. These stones came from far away—Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, other distant sources. The monastery was part of global economic networks.

The ceremonial vessels: Gold goblets, liturgical tools decorated with religious symbols.

Implication: Wealthy worship. The community valued beauty in religious practice, invested resources in making worship visually and materially impressive.

The variety: Not just one type of object but diverse items—jewelry, decorative pieces, ceremonial goods, possibly coins (exact inventory still being cataloged).

Implication: Wealth accumulated over time from multiple sources for multiple purposes. This wasn’t a single donation—this was systematic accumulation.

Each artifact is a data point telling us something about the monastery’s economic activity, cultural connections, and relationship with material wealth.

The Questions Archaeologists Are Now Asking

This discovery doesn’t just answer questions—it raises new ones:

How typical was this? Was this monastery unusually wealthy, or are most desert monasteries hiding similar treasures we haven’t found yet?

What happened to the monks? Why was the treasure never retrieved? Did the community die out? Were they killed? Did they flee and never return?

Where did the wealth come from? Donations? Payment for services? Pilgrimage revenue? We need to understand the economic model.

How did they justify it theologically? We have their wealth but not their explanation for possessing it. What did they tell themselves about why this was acceptable?

What else is hidden? If this site had treasure, what about the dozens of other monastery sites in the region? What haven’t we found yet?

How does this change our understanding of early Christian economics, monastic practice, and the relationship between spiritual ideals and material reality?

These questions will drive research for years. Each answer will probably generate more questions.

The Public Reaction: Pride and Complexity

When news of the discovery broke, reactions split predictably:

National pride: Israelis celebrating archaeological discoveries that connect them to the land’s history, seeing the treasure as part of their heritage.

Religious significance: Christians (especially Eastern Orthodox and Catholics with strong monastic traditions) viewing this as connection to their spiritual ancestors.

Academic excitement: Historians and archaeologists thrilled by new data that challenges and enriches our understanding of the past.

Economic interest: The gold has significant monetary value, though it will never be sold—it belongs in museums, not markets.

Tourism potential: The site will likely become tourist destination, bringing revenue to the region while requiring protection from over-visitation.

But there’s also complexity:

Whose heritage is this? The monastery was Christian, but it’s in Israel/Palestine, a contested region where every historical claim has political implications.

How should wealth be interpreted? Is this evidence of corruption and hypocrisy, or reasonable institutional management? The answer depends on your priors about monasticism.

What about modern monks? Contemporary monastic communities might feel defensive—does this discovery make historical monastics look bad? Or does it just show they were human?

The treasure means different things to different people. No interpretation is entirely wrong or entirely sufficient.

The Preservation Challenge

Now that the treasure is found, the real work begins: preservation and study.

Immediate conservation: Gold is stable, but cleaning, stabilizing, and protecting artifacts requires expert work. Conservation specialists are treating each piece.

Analysis: What’s the exact composition of the gold? Where did it originate? What techniques were used to craft it? Scientific analysis can answer these questions.

Documentation: Creating detailed records—photographs, measurements, descriptions—so scholars worldwide can study the finds.

Storage: Climate-controlled facilities protecting artifacts from deterioration while making them accessible for research.

Exhibition: Some pieces will eventually be displayed in museums, allowing public engagement with the discovery.

Site protection: The monastery itself needs protection from looters, vandals, and environmental damage while remaining accessible for continued archaeological work.

This is expensive, time-consuming work requiring expertise from multiple disciplines. The discovery is just the beginning.

What This Means for Future Archaeology

The gold treasure has implications beyond this specific site:

Reevaluating other sites: Archaeologists will look at other monasteries with fresh eyes, asking: What wealth might they have hidden? What assumptions about poverty should we question?

New methodologies: Using geophysical surveys and other technologies to find hidden caches without extensive excavation.

Economic focus: More attention to monasteries as economic institutions, not just spiritual ones. Understanding their role in Byzantine trade and finance.

Comparative studies: Looking at monastic wealth across regions and time periods—how did different communities handle the poverty-wealth tension?

Heritage preservation: Increased urgency to protect and study these sites before they’re lost to development, climate change, or looting.

The discovery opens research avenues that will keep archaeologists busy for decades.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Purity

Here’s what this discovery really reveals: Our narratives about the past are too clean.

We want early Christian monks to have been pure—rejecting the world, owning nothing, living spiritual ideals perfectly.

The reality: They were humans navigating competing values, institutional needs, and economic realities while trying to pursue spiritual ideals.

They believed in poverty while managing wealth. They valued simplicity while creating beauty. They sought isolation while maintaining networks. They rejected the world while engaging with it constantly.

This isn’t hypocrisy—it’s complexity. It’s the same tension every religious person navigates: How do you live spiritual values in material world? How do you pursue ideals while managing practical necessities?

The treasure is physical evidence that this tension is old. That the contradictions we see in contemporary Christianity—prosperity gospel preachers in private jets, megachurch wealth, institutional resources alongside preaching about sacrifice—have historical roots.

We’ve always struggled with this. The treasure proves it.

The Ending Without Resolution

Archaeologists found gold in a desert monastery that was supposed to be poor.

This challenges assumptions about early Christian monasticism, about the relationship between spiritual ideals and economic reality, about how communities actually functioned versus how they claimed to function.

It reveals that the past is more complicated than our narratives, that historical actors were humans navigating tensions and contradictions, that purity is a myth we project onto the past.

The treasure is still being studied. More discoveries will come. Our understanding will keep evolving.

But what we know now is enough to say: The story we told ourselves about desert monks was too simple.

They weren’t isolated ascetics completely disconnected from the world. They were participants in economic networks, managers of resources, navigators of the tension between spiritual ideals and institutional needs.

The gold proves it.

Hidden in the desert for over a thousand years, waiting to complicate our tidy narratives about the past.

Welcome to archaeology, where every discovery reminds us that history refuses to be simple.

The Judean Desert keeps its secrets well.

But eventually, it gives them up.

And they’re never quite what we expected.