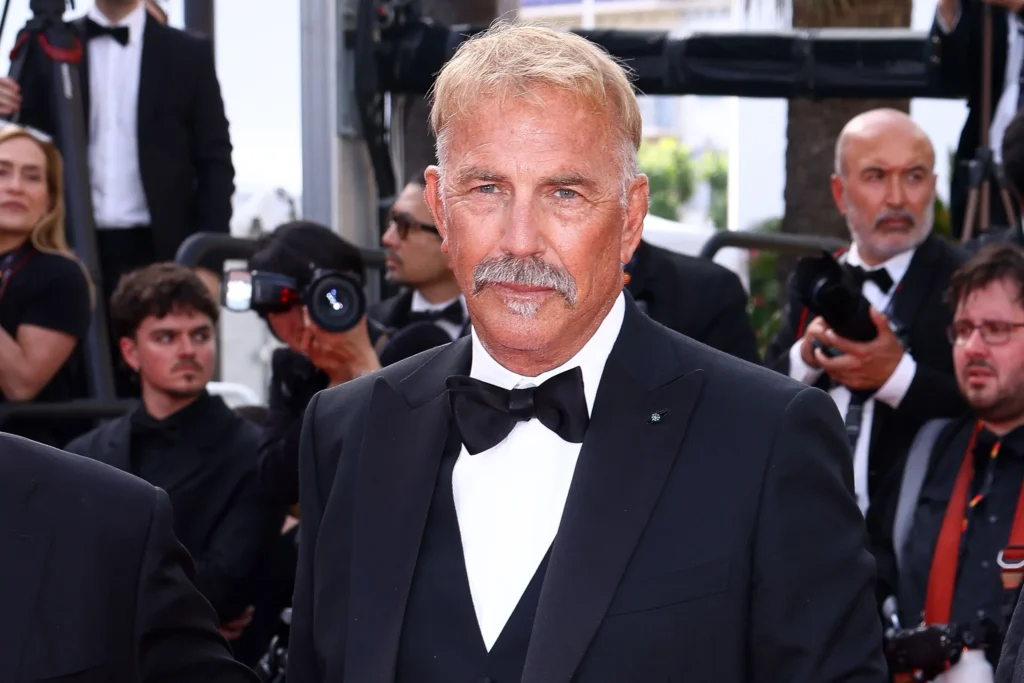

When Hollywood’s Leading Man Got Real About God: Kevin Costner’s Unexpected Faith Journey

kevin costner

The Actor Who Won’t Play It Safe

Kevin Costner has never been one to follow Hollywood’s script—on screen or off.

The man who danced with wolves, built a baseball diamond in a cornfield, and spent decades embodying rugged American masculinity has also spent his career doing something unusual for a major Hollywood star: talking openly about faith. Not the vague “spirituality” that celebrities mention to avoid offense. Not the carefully sanitized religious references that play well in Middle America without alienating coastal audiences.

Actual faith. Christian faith. The kind that shapes how you see the world and what stories you choose to tell.

His latest project, “The First Christmas,” puts that commitment front and center—a television special exploring the nativity story with the kind of reverence Hollywood typically reserves for superhero origin stories. It’s earnest, unapologetic, and entirely on-brand for an actor who’s spent decades refusing to separate his work from his beliefs.

Predictably, the response has been mixed. Some audiences appreciate Costner’s authenticity, grateful for a major star willing to engage seriously with religious themes. Others roll their eyes at what they see as another celebrity using their platform for evangelism.

But here’s what makes Costner’s approach interesting: he’s not preaching. He’s not trying to convert anyone or defend theological positions. He’s simply saying, “Faith has shaped my life and my work, and I’m not going to pretend otherwise.”

In an industry that often treats religious conviction as either quaint or dangerous, that honesty is remarkably rare.

The Foundation That Shaped Everything

Costner didn’t find faith later in life during some crisis or conversion experience. He was raised with it—the kind of embedded, foundational Christianity that shapes your worldview before you’re old enough to question it.

Born in 1955 to middle-class parents in California, Costner grew up in a household where faith wasn’t dramatic or performative—it was just there. His father worked for a utility company. His mother taught school. They went to church. They emphasized morality, integrity, treating people right. Standard mid-century American Christianity, the kind that informed values without making everything explicitly religious.

That foundation stuck. Even as Costner navigated Hollywood—an industry not exactly known for supporting traditional religious convictions—he carried those values with him. They influenced the roles he chose, the stories he wanted to tell, the way he approached his craft.

Look at his filmography and you’ll see it everywhere. “Field of Dreams” is essentially about faith—believing in something you can’t see, following a calling that doesn’t make logical sense, trusting that meaning exists beyond material reality. “Dances with Wolves” explores redemption and transformation. Even action films like “The Postman” grapple with sacrifice, hope, and the human need for purpose beyond survival.

Costner didn’t make “Christian movies” in the narrow sense. He made movies informed by a Christian worldview—which is actually more subversive. Instead of preaching to the choir, he embedded themes of faith, redemption, and moral struggle into mainstream entertainment that reached audiences who’d never watch explicitly religious content.

That’s been his approach throughout his career: not separating his faith from his work, but also not making his work only accessible to people who share his beliefs.

The Career Built on Conviction

Hollywood has a complicated relationship with religion. It loves religious stories when they’re historical epics or cultural phenomena. It’s less enthusiastic about actors who let faith inform their choices in ways that might limit commercial appeal.

Costner navigated this tension by being strategic. He didn’t make overtly preachy films. He didn’t alienate secular audiences by making everything explicitly Christian. But he also didn’t hide his values or pretend faith didn’t matter to him.

His early career was marked by rejections—the standard Hollywood struggle of paying dues, facing closed doors, wondering if success would ever come. During those years, Costner has said, faith was his anchor. When the industry kept saying no, when his future seemed uncertain, prayer provided grounding. The belief that his path had purpose, even when he couldn’t see it, kept him going.

That resilience paid off. By the late ’80s and early ’90s, Costner was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars. And even then—maybe especially then—he made choices that reflected his values. He could have coasted on action movies and romantic leads. Instead, he took risks on projects like “Dances with Wolves,” a three-hour epic about a Civil War soldier learning to see Indigenous people as fully human. It was a massive gamble that won seven Academy Awards.

The film’s themes—redemption, transformation, recognizing the divine in unexpected places—weren’t explicitly religious. But they reflected a worldview shaped by faith. The belief that people can change. That encountering the “other” can transform us. That sacrifice for something larger than yourself has meaning.

Throughout his career, Costner has consistently chosen projects that grapple with these themes. Not always successfully—he’s made plenty of commercial flops. But always intentionally. His work reflects someone trying to tell stories that matter, that explore the deeper questions of human existence.

When Personal Tragedy Deepened Faith

Success doesn’t insulate you from suffering. Costner learned that the hard way.

Throughout his life, he’s faced the losses that mark any long existence—loved ones dying, relationships failing, plans collapsing. In interviews, he’s spoken candidly about how grief drove him deeper into faith. How loss forced him to grapple with questions that can’t be answered with logic or avoided through distraction.

When you face profound loss, you either abandon faith or transform it. Costner’s faith deepened. It became less about certainty and more about trust. Less about having answers and more about finding meaning in the questions.

He’s described prayer during dark periods as essential—not because it magically fixed problems, but because it provided a way to process pain that acknowledged both suffering and hope. Faith became his framework for making sense of experiences that didn’t make sense.

This evolution is visible in his later work. His characters became more complex, more broken, more obviously grappling with failure and redemption. The easy heroism of his early films gave way to more nuanced portrayals of men trying to find purpose after loss.

That authenticity resonates because it’s not performative. Costner isn’t using faith as branding or spiritual struggles as content. He’s a person whose beliefs have been tested and refined by real life, and that shows in his work.

“The First Christmas”: Going All In

Which brings us to “The First Christmas”—Costner’s most explicitly faith-focused project to date.

A television special exploring the nativity story is… not an obvious choice for a major Hollywood star in 2024. Religious content has a ceiling. It will appeal to Christian audiences but likely alienate secular viewers. It’s the definition of niche.

Costner did it anyway.

The special presents the Christmas story with a straightforward reverence that’s almost startling in our irony-saturated culture. No winking at the camera. No hedging about “diverse perspectives.” Just an earnest exploration of the narrative that Christianity is built on.

For believers, this is refreshing. Finally, a major star treating their faith with the seriousness it deserves, not relegating it to private belief while maintaining public neutrality.

For skeptics, it’s… a lot. An uncritical presentation of religious narrative as historical fact feels like propaganda, or at best, an expensive Sunday school lesson.

Costner anticipated this divide. In promotional interviews, he’s been clear: this isn’t for everyone. It’s for people who find the Christmas story meaningful, who want to engage with it deeply rather than just using it as seasonal decoration.

He’s also been clear that he’s not trying to convert anyone. This isn’t evangelism disguised as entertainment. It’s an exploration of a story that has shaped Western civilization, presented for an audience that still finds it compelling.

The project reflects Costner’s consistent approach: I’m not hiding my faith, but I’m also not demanding you share it. Here’s what I believe and why it matters. Engage with it or don’t.

When Fame Meets Faith

Celebrity culture and religious conviction make strange bedfellows.

We want celebrities to be authentic—except when their authenticity reveals beliefs we don’t share. We celebrate vulnerability—until that vulnerability is spiritual. We praise artists who draw from personal experience—unless that experience is shaped by faith.

Costner navigates this by refusing the binary. He doesn’t play the persecuted Christian martyr, claiming Hollywood discriminates against believers. He also doesn’t downplay his faith to maintain broader appeal. He just… is who he is, and lets audiences respond however they will.

This approach has power precisely because it’s not combative. Costner isn’t fighting culture wars or claiming victimhood. He’s modeling something different: the possibility of being deeply religious in a secular industry without being either defensive or proselytizing.

For Christian audiences, especially younger believers navigating secular workplaces, this representation matters enormously. Here’s someone successful who didn’t compartmentalize faith. Who didn’t treat belief as private and irrelevant to public work. Who integrated values and vocation without making everything explicitly religious.

For secular audiences, Costner offers something equally valuable: evidence that you can take religious people seriously even if you don’t share their beliefs. That faith can inform good work without requiring agreement. That spiritual conviction doesn’t equal intellectual weakness.

The Stories We Tell Ourselves

At the core of Costner’s career is a conviction about storytelling: that it matters. That the narratives we consume shape how we see the world and our place in it. That entertainment isn’t just distraction—it’s meaning-making.

This belief is deeply rooted in Christian tradition. The Bible is primarily stories. Jesus taught through parables. Faith communities have always understood that narrative shapes belief more powerfully than argument.

Costner approaches filmmaking with this understanding. He’s not trying to make art that’s separate from meaning, or entertainment divorced from values. He’s trying to tell stories that help people make sense of life—stories about redemption and sacrifice and hope and transformation.

This puts him at odds with much of contemporary Hollywood, which often views explicit meaning with suspicion. Modern prestige cinema tends toward ambiguity, moral complexity without resolution, questions without answers. There’s value in that approach—life is complex and ambiguous.

But Costner represents an alternative tradition: storytelling that acknowledges complexity while still reaching for meaning. That wrestles with hard questions but believes answers exist. That presents moral struggles without abandoning the possibility of moral clarity.

His faith informs this approach. Not because he’s making “Christian propaganda,” but because Christianity provides a framework for understanding human nature, suffering, redemption, and hope. Those themes are universal—they resonate even with audiences who don’t share his theological commitments.

The Community Beyond the Camera

Costner’s faith isn’t just personal conviction—it’s expressed through action.

Throughout his career, he’s aligned with faith-based charities and community initiatives. He’s used his platform to raise awareness and funds for causes rooted in Christian values: supporting families, serving the poor, promoting reconciliation and healing.

These aren’t high-profile publicity stunts. They’re quiet, consistent engagement with communities that share his values. Church groups. Non-profits serving vulnerable populations. Organizations doing unglamorous work that reflects the gospel’s call to serve “the least of these.”

This engagement reveals something important: Costner’s faith isn’t abstract or purely intellectual. It’s embodied in relationships and action. He’s not just a celebrity who talks about belief—he’s someone actively participating in faith communities and their work.

This matters because it addresses one of the valid criticisms of celebrity Christianity: that it’s all talk, no action. That famous people use faith as branding without actually living according to their professed values.

Costner’s consistent involvement with faith-based initiatives suggests his conviction is real. He’s putting time, resources, and reputation where his mouth is. He’s not just making content about faith—he’s engaged in the messy, unglamorous work of actually living it out in community.

When the Audience Pushes Back

Not everyone appreciates Costner’s openness about faith. The responses to “The First Christmas” and his broader faith expression reveal the complicated landscape of religion in public life.

Christian audiences largely celebrate him. Here’s a major star who hasn’t abandoned faith for fame, who uses his platform to explore spiritual themes, who models integration of belief and vocation. They see him as rare representation in an industry that often treats their worldview with contempt or condescension.

But secular audiences and critics are more mixed. Some appreciate his honesty even if they don’t share his beliefs. Others find his faith expression off-putting—too earnest, too uncritical, too willing to present religious narrative as meaningful rather than quaint artifact.

The harshest criticism suggests Costner is using his celebrity to proselytize, that projects like “The First Christmas” are evangelism disguised as entertainment. That his influence gives him disproportionate platform for promoting beliefs many Americans don’t share.

These responses reveal our cultural discomfort with public faith expression. We’re fine with religion as private belief or cultural identity. We struggle when people of influence present faith as serious, important, deserving engagement from people who don’t share it.

Costner seems unbothered by this tension. He’s not trying to please everyone or avoid offense. He’s simply being honest about what matters to him, and letting audiences respond however they will.

The Legacy Being Written

As Costner’s career enters its later chapters, his faith-informed approach to storytelling stands out.

He’s carved a unique path: neither abandoning faith to succeed in secular Hollywood, nor retreating into explicitly Christian entertainment that only reaches believers. He’s maintained both artistic credibility and spiritual authenticity, proving it’s possible to integrate faith and mainstream success.

His filmography will be remembered for many things—iconic roles, directorial ambition, willingness to take creative risks. But increasingly, it will also be remembered as work informed by consistent values. Stories that grapple with meaning, redemption, sacrifice, hope. Films that reflect a worldview shaped by Christian conviction without being reducible to that conviction.

“The First Christmas” represents a culmination of this approach. Costner is at a point in his career where he can be completely explicit about faith without worrying about commercial consequences. He’s earned the freedom to make exactly the projects he wants, and he’s choosing to explore the religious narrative that has shaped his life.

This matters for several reasons. It normalizes faith expression from public figures in ways that aren’t defensive or combative. It demonstrates that spiritual conviction can coexist with artistic excellence. It offers both believers and skeptics a model of how to engage with people whose worldview differs from yours without requiring agreement or capitulation.

The Uncomfortable Invitation

Here’s what Costner’s career ultimately offers: an invitation to take faith seriously.

Not to agree with it. Not to convert or adopt his beliefs. But to recognize that for millions of people—including highly successful, intelligent, creative people—religious faith is central to how they understand themselves and the world.

That invitation makes secular audiences uncomfortable because it challenges the assumption that serious, thoughtful people have moved beyond religion. It complicates the narrative that faith is declining because people are getting smarter and realizing it’s all superstition.

Costner stands as evidence that someone can be successful, intelligent, and creative while maintaining deep religious conviction. That faith can inform excellent work without making it narrowly religious. That spiritual belief can be sophisticated and thoughtful rather than simplistic and defensive.

For believers, especially those in secular workplaces or industries, this representation provides both validation and model. You don’t have to hide your faith or compartmentalize your life. You can be fully yourself—religious conviction and all—while also excelling in secular spaces.

For skeptics, Costner offers a challenge: engage with people of faith charitably. Recognize that religious conviction can be thoughtful, that spiritual meaning-making is legitimate even if you don’t share it, that faith informs valuable perspectives worth considering.

The Story Still Being Told

Kevin Costner’s faith journey isn’t finished. At 69, he’s still working, still choosing projects, still navigating the intersection of belief and public life.

“The First Christmas” won’t be his last faith-informed project. More will come—some explicitly religious, others embedding spiritual themes in mainstream entertainment. He’ll keep telling stories shaped by Christian worldview while inviting audiences of all beliefs to engage.

The responses will remain mixed. Some will celebrate his authenticity and appreciate his willingness to explore faith publicly. Others will criticize him for using his platform to promote religious views they don’t share.

But Costner seems at peace with this dynamic. He’s not trying to win everyone over or avoid all criticism. He’s simply being honest about who he is and what matters to him, then doing the work that reflects those values.

In an industry and culture that often demands you choose between authenticity and broad appeal, Costner has carved out a third option: be fully yourself and let the audience decide whether they’re interested.

That approach—refusing to hide your convictions while also refusing to force them on others—might be the most valuable thing his career offers. Not his specific beliefs, but his modeling of how to hold strong convictions in pluralistic spaces without becoming either defensive or aggressive.

It’s a way of being religious in public life that we desperately need more of: confident without being combative, authentic without being evangelical, serious without being self-righteous.

That’s the real legacy Kevin Costner is building. Not just films about faith, but a life that demonstrates faith can be integrated with excellence, conviction with creativity, belief with broad appeal.

The story is still being written. But the themes are clear: integrity matters, authenticity counts, and faith—when lived honestly—can inform work that resonates far beyond those who share it.

That’s a narrative worth celebrating, whether you believe in God or not.